[ad_1]

The basic human need to get along with others results in the formation of extreme political groupings, according to a study from Dartmouth College.

The findings, published in the journal Royal Society Open Science, add to the widening body of research on the behavior of social and political networks.

The Dartmouth research demonstrates that individuals often ignore essential information when forming opinions, resulting in partisanship and division. By explaining the underlying factors responsible for societal splits, the study provides a deeper understanding of current divides in the United States.

Three factors drive the formation of social and political groups according to the research: social pressure to have stronger opinions, the relationship of an individual’s opinions to those of their social neighbors, and the benefits of having social connections.

A key idea studied in the paper is that people choose their opinions and their connections to avoid differences of opinion with their social neighbors. By joining like-minded groups, individuals also prevent the psychological stress, or “cognitive dissonance,” of considering opinions that do not match their own.

“Human social tendencies are what form the foundation of that political behavior,” said Tucker Evans, a senior at Dartmouth who led the study. “Ultimately, strong relationships can have more value than hard evidence, even for things that some would take as proven fact.”

To conduct the study, the team developed a mathematical model that considers how individuals receive information as well as the social pressures they feel to conform to particular political views. The model helped the researchers understand how divisions form and how they intensify into greater partisanship and increased polarization.

In the aftermath of the recent U.S. mid-term elections, the study helps explain how partisan groupings evolve to become extreme, ultimately resulting in the formation of “echo chambers” in which political beliefs go unchallenged and increase in strength.

“Understanding opinion evolution is a major research concern and is essential in the context of modern politics,” said Feng Fu, an assistant professor of mathematics at Dartmouth that advised on the research. “We wanted to know how the structure of groups can change the way individuals develop their beliefs, and how those beliefs can then develop into blocs like those we see on social media.”

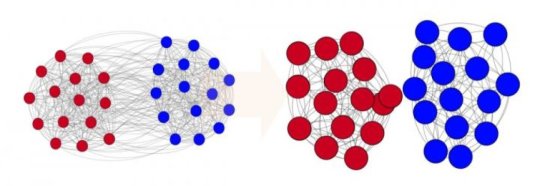

The team tracked how small societal shifts improve the stability of groups. Given the right conditions, these changes lead to clustering of individuals that share the same opinions and a division into distinct populations. This self-reinforcing structure copies that of partisan bubbles seen in politics and some media.

According to the research paper, interactions within a social network create complex structures similar to political subcommunities that develop on ideological grounds “from Democrats and Republicans to pro-vaccination and anti-vaccination groups.”

“In countries like the U.S., when individuals act to minimize disagreement and forge unity within their social groups, the result can be complete division at the national level,” said Evans. “Understanding how this happens could help people act in a way that is more beneficial to the common good.

To validate the results, researchers studied voting records of the U.S. House of Representatives from 1949-2011. According to the team, the congressional data supports the use of the model to understand real-world partisanship.

The Dartmouth research paper builds on existing studies that identify the characteristics of social networks. The new study increases understanding by demonstrating how certain tendencies influence individuals within the social networks.

In the future, the team will study how the validity of particular opinions comes into play and when evidence starts to matter in the formation of opinions. Future research will also consider the application of multiple levels of opinion, delving into the world of belief ‘systems’ in contrast to single beliefs.

Funding for this research was provided by the Presidential Scholars Program, the Dartmouth Faculty Startup Fund, Walter & Constance Burke Research Initiation Award, and the Dartmouth COPE funds.

Story Source:

Materials provided by Dartmouth College. Note: Content may be edited for style and length.

[ad_2]