[ad_1]

Individuals have as big a role to play in tackling climate change as major corporations but only if they can be encouraged to make significant lifestyle changes by effective government policy, a major new European study co-authored by a University of Sussex academic has found.

The study notes that voluntary lifestyle choices by well-meaning individuals would only achieve around half the required emission reductions needed to hit the 1.5 C Paris Agreement goal. But the authors suggest that Paris targets could be achieved if voluntary choices were combined with policies that target behavioural change, particularly around eating meat and using fewer cars and airplanes.

The study’s authors say the international climate policy debate has so far focused mainly on technology and economic incentives, relegating behaviour change to a voluntary add-on. This is despite the fact behavioural change has the potential for far greater emission reductions than the political pledges made under the Paris Accord.

The study, written by academics from 11 institutions including the University of Sussex, investigated the preferences for reducing household emissions, responsible for about 70% of global greenhouse gas emissions. It involved hundreds of families in four European cities using a specially-designed simulation tool to indicate carbon and money savings from 65 lifestyle choices combined with in-depth surveys with household members.

It found public support for policy initiatives that encouraged more sustainable practices around food production but resistance to initiatives that restricted personal mobility and transport options. The study also found that ironically the areas where greatest lifestyle changes were required and the largest carbon footprints produced, such as aviation and changes to diet, had received the lowest policy attention to date.

Lead author Ghislain Dubois, founder of the TEC Conseil in France, said: “Our research proves that if supported by adequate policies, households can have a decisive contribution to the Paris agreement objectives. This is largely ignored by current climate policies and negotiations, which rely only on macro-economics and technology. We should dare envisaging and doing research on taboos like consumption reduction or sobriety. When you consider the impacts on CO2 emissions, but also on households’ budgets and the potential co-benefits, it is worth it.”

Professor Benjamin Sovacool, second author of the study and Director of the Sussex Energy Group at the University of Sussex, added: “Our study underscores the contradictions we all have in balancing climate change with other priorities. We want to fight climate change, but stick to eating meat and driving our cars. There are certain changes we can make voluntarily but beyond that we need policy to step in.”

The study, published in the upcoming June edition of Energy Research and Social Science, found that the greater the potential actions have to reduce emissions, the less households were willing to implement them. In these areas “forced” solutions such as a considerably higher carbon tax on fuel and regulations encouraging food producers to reduce packaging or increase local and organic farming in addition to voluntary measures will be needed, the academics warn.

Carlo Aall, co-author of the study from the Western Norway Research Institute, said: “There is political room for taking a tougher stand on supporting economically and regulating household consumption to become more climate friendly. Meat consumption and long air trips in particular need to be addressed.”

Alina Herrmann, co-author from the Heidelberg Institute for Global Health said: “Strikingly, people were very open to climate friendly solutions in the food and recycling sector. We have found strong support for less packaged food, more sustainable food production and moderate reduction of meat consumption in our study population. Many participants even wished for external support to make such sustainable choices easier for them.”

However, in areas such as mobility, the authors recommend limiting the availability of greenhouse gas-intensive consumption through regulative instruments such bans, restrictions or increased taxes; balanced with making low-carbon alternatives more readily available.

Dr Hermann added: “Changing mobility behaviour was seen as incredibly difficult. To gain acceptance for reduced mobility as part of societal transformation in the face of climate change, and entirely new public discourse would be needed.”

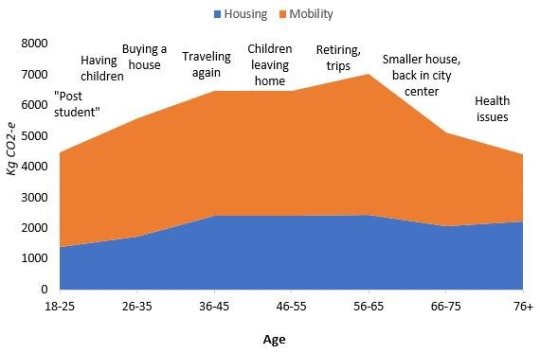

Responses from the study revealed household carbon footprints are not static but can fluctuate significantly with major life events such as having children, experiencing illness or retiring.

The authors recommend that targeted interventions at these milestones could be highly effective in bringing about long-lasting change and suggested that intermediaries at these milestones, such as estate agents, car sales staff and retirement planners, could all play a much more active role in identifying carbon-reducing options.

[ad_2]