[ad_1]

New data from the STAR experiment a the Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider (RHIC) add detail — and complexity — to an intriguing puzzle that scientists have been seeking to solve: how the building blocks that make up a proton contribute to its spin. The results, just published as a rapid communication in the journal Physical Review D, reveal definitively for the first time that different “flavors” of antiquarks contribute differently to the proton’s overall spin — and in a way that’s opposite to those flavors’ relative abundance.

“This measurement shows that the quark piece of the proton spin puzzle is made of several pieces,” said James Drachenberg, a deputy spokesperson for STAR from Abilene Christian University. “It’s not a boring puzzle; it’s not evenly divided. There’s a more complicated picture and this result is giving us the first glimpse of what that picture looks like.”

It’s not the first time that scientists’ view of proton spin has changed. There was a full-blown spin “crisis” in the 1980s when an experiment at the European Center for Nuclear Research (CERN) revealed that the sum of quark and antiquark spins within a proton could account for, at best, a quarter of the overall spin. RHIC, a U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science user facility for nuclear physics research at Brookhaven National Laboratory, was built in part so scientists could measure the contributions of other components, including antiquarks and gluons (which “glue” together, or bind, the quarks and antiquarks to form particles such as protons and neutrons).

Antiquarks have only a fleeting existence. They form as quark-antiquark pairs when gluons split.

“We call these pairs the quark sea,” Drachenberg said. “At any given instant, you have quarks, gluons, and a sea of quark-antiquark pairs that contribute in some way to the description of the proton. We understand the role these sea quarks play in some respects, but not in respect to spin.”

Exploring flavor in the sea

One key consideration is whether different “flavors” of sea quarks contribute to spin differently.

Quarks come in six flavors — the up and down varieties that make up the protons and neutrons of ordinary visible matter, and four other more exotic species. Splitting gluons can produce up quark/antiquark pairs, down quark/antiquark pairs — and sometimes even more exotic quark/antiquark pairs.

“There is no reason why a gluon would prefer to split into one or the other of these flavors,” said Ernst Sichtermann, a STAR collaborator from DOE’s Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (LBNL) who played a lead role in the sea quark research. “We’d expect equal numbers [of up and down pairs], but that’s not what we are seeing.” Measurements at CERN and DOE’s Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory have consistently found more down antiquarks than up antiquarks.

“Because there is this surprise — an asymmetry in the abundance of these two flavors — we thought there might also be a surprise in their role in spin,” Drachenberg said. Indeed, earlier results from RHIC indicated there might be a difference in how the two flavors contribute to spin, encouraging the STAR team to do more experiments.

Delivering on spin goals

This result represents the accumulation of data from the 20-year RHIC spin program. It is the final result from one of the two initial pillars motivating the spin program at the dawn of RHIC.

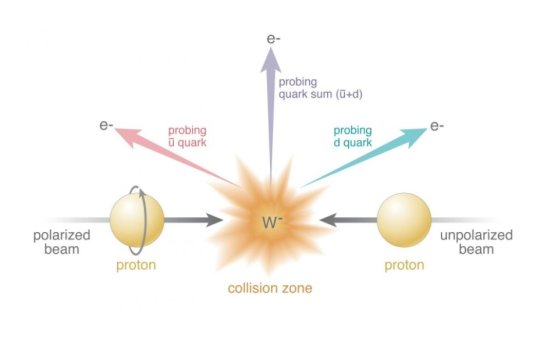

For all of these experiments, STAR analyzed the results of polarized proton collisions at RHIC — collisions where the overall spin direction of RHIC’s two beams of protons was aligned in particular ways. Looking for differences in the number of certain particles produced when the spin direction of one polarized proton beam is flipped can be used to track the spin alignment of various constituents — and therefore their contributions to overall proton spin.

For the sea quark measurements, STAR physicists counted electrons and positrons — antimatter versions of electrons that are the same in every way except that they carry a positive rather than a negative electric charge. The electrons and positrons come from the decay of particles called W bosons, which also come in negative and positive varieties, depending on whether they contain an up or down antiquark. The difference in the number of electrons produced when the colliding proton’s spin direction is flipped indicates a difference in W- production and serves as a stand in for measuring the spin alignment of the up antiquarks. Similarly, the difference in positrons comes from a difference in W+ production and serves the stand-in role for measuring the spin contribution of down antiquarks.

New detector, added precision

The latest data include signals captured by STAR’s endcap calorimeter, which picks up particles traveling close to the beamline forward and rearward from each collision. With this new data added to data from particles emerging perpendicular to the collision zone the scientists have narrowed the uncertainty in their results. The data show definitively, for the first time, that the spins of up antiquarks make a greater contribution to overall proton spin than the spins of down antiquarks.

“This ‘flavor asymmetry,’ as scientists call it, is surprising in itself, but even more so considering there are more down antiquarks than up antiquarks,” said Qinghua Xu of Shandong University, another lead scientist who supervised one of the graduate students whose analysis was essential to the paper.

As Sichtermann noted, “If you go back to the original proton spin puzzle, where we learned that the sum of the quark and antiquark spins accounts for just a fraction of proton spin, the next questions are what is the gluon contribution? What is the contribution from the orbital motion of the quarks and gluons? But also, why is the quark contribution so small? Is it because of a cancellation between quark and antiquark spin contributions? Or is it because of differences between different quark flavors?

“Previous RHIC results have shown that gluons play a significant role in proton spin. This new analysis gives a clear indication that the sea also plays a significant role. It is far more complicated than just gluons splitting into any flavor you like — and a very good reason to look deeper into the sea.”

Bernd Surrow, a physicist from Temple University who helped develop the W boson method and supervised two of the graduate students whose analyses led to the new publication, agrees. “After multiple years of experimental work at RHIC, this exciting new result provides a substantially deeper understanding of the quantum fluctuations of quarks and gluons inside the proton. These are the kinds of fundamental questions that attract young minds — the students who will continue to expand the limits of our knowledge.”

Additional STAR measurements might offer insight into the spin contributions of exotic quark/antiquark pairs. In addition, U.S. scientists hope to delve deeper into the spin mystery at a proposed future Electron-Ion Collider. This particle accelerator would use electrons to directly probe the spin structure of the internal components of a proton — and should ultimately solve the proton spin puzzle.

Why study proton spin?

Spin is a fundamental property of particles, as essential to a particle’s identity as its electric charge. Because particles have spin, they can act like tiny magnets with a particular polarity. Aligning and flipping the polarity of proton spin is the basis for technologies like magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). But scientists are still striving to understand how the inner building blocks of protons — the quarks and gluons and sea of quark-antiquark pairs, as well as their motion within the proton — build up the overall particle’s spin. Understanding how proton spin arises from its inner building blocks may help scientists understand how the complex interactions within the proton give rise to its overall structure, and in turn to the nuclear structure of the atoms that make up nearly all visible matter in our universe — everything from stars to planets to people.

[ad_2]