[ad_1]

There is often a pronounced symmetry when you look at the lattice of crystals: it doesn’t matter where you look — the atoms are uniformly arranged in every direction. This behavior was also to be expected by a crystal, which physicists at the Helmholtz-Zentrum Dresden-Rossendorf (HZDR), the University of Warsaw and the Polish Academy of Sciences produced, using a special process: a compound from an indium arsenide semiconductor, spiked with some iron. The material, however, did not adhere to perfect symmetry. The iron formed two-dimensional, lamellar-shaped structures in the crystal that lent the material a striking property: it became magnetic. In the long term, the result could be vital in understanding superconductors.

“Using the possibilities of our Ion Beam Center, we fired fast iron ions at a crystal made of indium arsenide, a semiconductor made of indium and arsenic,” says Dr. Shengqiang Zhou, physicist at the HZDR Institute of Ion Beam Physics and Materials Research. “The iron penetrated approximately one hundred nanometers deep into the crystal surface.” The iron ions remained in the minority — they constituted only a few percent in the surface. The researchers then fired light pulses at the crystal using a laser. The flashes were ultra-short so that only the surface melted. “For much less than a microsecond, the top one hundred nanometers were a hot soup, whereas the crystal underneath remained cold and well ordered,” Zhou says, describing the result.

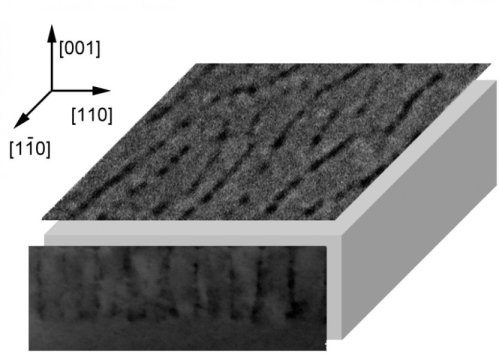

The crystal surface cooled again just a blink of an eye after the laser bombardment. Something unusual had happened: the surface had essentially reverted back to the indium arsenide lattice structure. The cooling, however, was so rapid that the iron atoms did not have sufficient time to find and occupy a regular lattice state in the crystal. Instead, the metal atoms joined forces with their peers to form remarkable structures — small two-dimensional lamellae, arranged in parallel.

“It came as a surprise that the iron atoms were arranged in this manner,” says Zhou. “We were thus able to create such a lamellar structure for the first time globally.” When the experts examined the newly created material more closely, they determined that it had become magnetic due to the influence of iron. The researchers from Poland and Germany also managed to theoretically describe the process and simulate it on the computer. “The iron atoms arranged themselves into a lamellar structure because this was energetically the most favorable state they could take in the brief period of time,” says Prof. Tomasz Dietl from the International Research Center MagTop at the Polish Academy of Sciences, summarizing the result of the calculations.

The result could be relevant in, for example, understanding superconductors — a class of materials that can conduct electricity entirely without loss. “Lamellae-like structures can also be found in many superconducting materials,” explains Zhou. “Our compound could therefore serve as a model system and help in better understanding superconductor behavior.” This could perhaps also serve to optimize their properties: in order for superconductors to work, they must currently be cooled to comparatively low temperatures of, for example, minus two hundred degrees Celsius. The aim of many experts is to increase these temperatures gradually — until they find a dream material, which loses its electrical resistance even at normal ambient temperatures.

Story Source:

Materials provided by Helmholtz-Zentrum Dresden-Rossendorf. Note: Content may be edited for style and length.

[ad_2]