[ad_1]

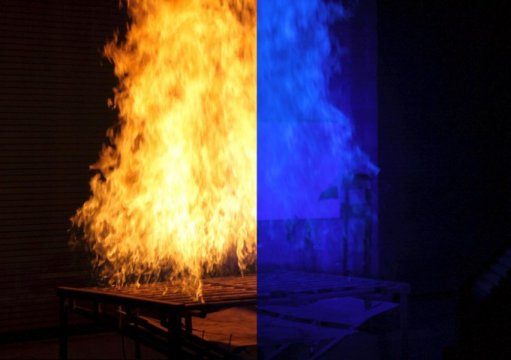

Researchers at the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) have demonstrated that ordinary blue light can be used to significantly improve the ability to see objects engulfed by large, non-smoky natural gas fires — like those used in laboratory fire studies and fire-resistance standards testing.

As described in a new paper in the journal Fire Technology, the NIST blue-light imaging method can be a useful tool for obtaining visual data from large test fires where high temperatures could disable or destroy conventional electrical and mechanical sensors.

The method provides detailed information to researchers using optical analysis such as digital image correlation (DIC), a technique that compares successive images of an object as it deforms under the influence of applied forces such as strain or heat. By precisely measuring the movement of individual pixels from one image to the next, scientists gain valuable insight about how the material responds over time, including behaviors such as strain, displacement, deformation and even the microscopic beginnings of failure.

However, using DIC to study how fire affects structural materials presents a special challenge: How does one get images with the level of clarity needed for research when bright, rapidly moving flames are between the sample and the camera?

“Fire makes imaging in the visible spectrum difficult in three ways, with the signal being totally blocked by soot and smoke, obscured by the intensity of the light emitted by the flames, and distorted by the thermal gradients in the hot air that bend, or refract, light,” said Matt Hoehler, a research structural engineer at NIST’s National Fire Research Laboratory (NFRL) and one of the authors of the new paper. “Because we often use low-soot, non-smoky gas fires in our tests, we only had to overcome the problems of brightness and distortion.”

To do that, Hoehler and colleague Chris Smith, a research engineer formerly with NIST and now at Berkshire Hathaway Specialty Insurance, borrowed a trick from the glass and steel industry where manufacturers monitor the physical characteristics of materials during production while they are still hot and glowing.

“Glass and steel manufacturers often use blue-light lasers to contend with the red light given off by glowing hot materials that can, in essence, blind their sensors,” Hoehler said. “We figured if it works with heated materials, it could work with flaming ones as well.”

Hoehler and Smith used commercially available and inexpensive blue light-emitting diode (LED) lights with a narrow-spectrum wavelength around 450 nanometers for their experiment.

Initially, the researchers placed a target object behind the gas-fueled test fire and illuminated it in three ways: by white light alone, by blue light directed through the flames and by blue light with an optical filter placed in front of the camera. The third option proved best, reducing the observed intensity of the flame by 10,000-fold and yielding highly detailed images.

However, just seeing the target wasn’t enough to make the blue-light method work for DIC analysis, Hoehler said. The researchers also had to reduce the image distortion caused by the refraction of light by the flame — a problem akin to the “broken pencil” illusion seen when a pencil is placed in a glass of water.

“Luckily, the behaviors we want DIC to reveal, such as strain and deformation in a heated steel beam, are slow processes relative to the flame-induced distortion, so we just need to acquire a lot of images, collect large amounts of data and mathematically average the measurements to improve their accuracy,” Hoehler explained.

To validate the effectiveness of their imagining method, Hoehler and Smith, along with Canadian collaborators John Gales and Seth Gatien, applied it to two large-scale tests. The first examined how fire bends steel beams and the other looked at what happens when partial combustion occurs, progressively charring a wooden panel. For both, the imaging was greatly improved.

“In fact, in the case of material charring, we feel that blue-light imaging may one day help improve standard test methods,” Hoehler said. “Using blue light and optical filtering, we can actually see charring that is normally hidden behind the flames in a standard test. The clearer view combined with digital imaging improves the accuracy of measurements of the char location in time and space.”

Hoehler also has been involved in the development of a second method for imaging objects through fire with colleagues at NIST’s Boulder, Colorado, laboratories. In an upcoming NIST paper in the journal Optica, the researchers demonstrate a laser detection and ranging (LADAR) system for measuring volume change and movement of 3D objects melting in flames, even though moderate amounts of soot and smoke.

[ad_2]