[ad_1]

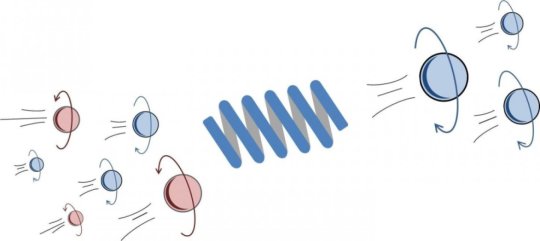

When it comes to realizing low-power electronic devices, spintronics looks promising. Spin is a quantum-mechanical property of electrons that can best be imagined as electrons spinning around their own axis, causing them to behave like small compass needles. A current of electron spins could be used in electronic devices. However, to generate a suitable spin current, you need a relatively large magnet. An alternative method that uses a special type of molecule has been proposed, but the big question is: does it work? University of Groningen Ph.D. student Xu Yang has constructed a theoretical model which describes how to put this new method to the test.

Spin can have two directions, usually designated as ‘up’ and ‘down’. In a normal electron current, there are equal quantities of both spin directions, but if you want to use spin to transfer information, you need a surplus of one direction. This is usually done by injecting electrons into a spintronic device through a ferromagnet, which will favor the passage of one type of spin. ‘But ferromagnets are bulky compared to the other components’, says Yang.

DNA

That is why a 2011 breakthrough that was published in Science is attracting increased attention. ‘This paper described how passing a current through a monolayer of DNA double helices would favor one type of spin.’ The DNA molecules are chiral, which means they can exist in two forms which are each other’s mirror image — like a left and right hand. The phenomenon was dubbed Chiral Induced Spin Selectivity (CISS), and over the last few years, several experiments were published which allegedly showed this CISS effect, even in electronic devices.

‘But we were not so sure’, explains Yang. One type of experiment used a monolayer of DNA fragments, whereas another used an atomic force microscope to measure the current through single molecules. Different chiral helices were used in the experiments. ‘The models explaining why these molecules would favor one of the spins made lots of assumptions, for example about the shape of the molecules and the path the electrons took.’

Circuits

So Yang set out to create a generic model which could describe how spins would pass through different circuits under a linear regime (i.e. the regime that electronic devices operate in). ‘These models were based on universal rules, independent of the type of molecule’, explains Yang. One such rule is charge conservation, which states that every electron that enters a circuit should eventually exit it. A second rule is reciprocity, which states that if you swap the roles of the voltage and current contacts in a circuit, the signal should remain the same.

Next, Yang described how these rules would affect the transmission and reflection of spins in different components, for example, a chiral molecule and a ferromagnet between two contacts. The universal rules enabled him to calculate what happened to the spins in these components. He then used the components to model more-complex circuits. This allowed him to calculate what to expect if the chiral molecules showed the CISS effect and what to expect if they did not.

Convincing

When he modeled the CISS experiments published so far, Yang found that some are, indeed, inconclusive. ‘These experiments aren’t convincing enough. They do not show a difference between molecules with and without CISS, at least not in the linear regime of electronic devices.’ Furthermore, any device using just two contacts will fail to prove the existence of CISS. The good news is that Yang designed circuits with four contacts that will allow scientists to detect the CISS effect in electronic devices. ‘I am currently also working on such a circuit, but as it is made up of molecular building blocks, this is quite a challenge.’

By publishing his model now, Yang hopes that more scientists will start building the circuits he has proposed, and will finally be able to prove the existence of CISS in electronic devices. ‘This would be a great contribution to society, as it may enable a whole new approach to the future of electronics.’

Story Source:

Materials provided by University of Groningen. Note: Content may be edited for style and length.

[ad_2]