[ad_1]

Scientists from the Max Born Institute (MBI) have developed the first refractive lens that focuses extreme ultraviolet beams. Instead of using a glass lens, which is non-transparent in the extreme-ultraviolet region, the researchers have demonstrated a lens that is formed by a jet of atoms. The results, which provide novel opportunities for the imaging of biological samples on the shortest timescales, were published in Nature.

A tree trunk partly submerged in water appears to be bent. Since hundreds of years people know that this is caused by refraction, i.e. the light changes its direction when traveling from one medium (water) to another (air) at an angle. Refraction is also the underlying physical principle behind lenses which play an indispensable role in everyday life: They are a part of the human eye, they are used as glasses, contact lenses, as camera objectives and for controlling laser beams.

Following the discovery of new regions of the electromagnetic spectrum such as ultraviolet (UV) and X-ray radiation, refractive lenses were developed that are specifically adapted to these spectral regions. Electromagnetic radiation in the extreme-ultraviolet (XUV) region is, however, somewhat special. It occupies the wavelength range between the UV and X-ray domains, but unlike the two latter types of radiation, it can only travel in vacuum or strongly rarefied gases. Nowadays XUV beams are widely used in semiconductor lithography as well as in fundamental research to understand and control the structure and dynamics of matter. They enable the generation of the shortest human made light pulses with attosecond durations (an attosecond is one billionth of a billionth of a second). However, in spite of the large number of XUV sources and applications, no XUV lenses have existed up to now. The reason is that XUV radiation is strongly absorbed by any solid or liquid material and simply cannot pass through conventional lenses.

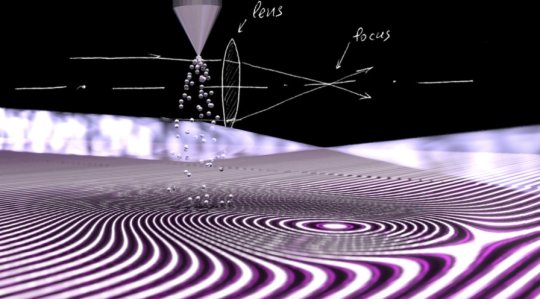

In order to focus XUV beams, a team of MBI researchers have taken a different approach: They replaced a glass lens with that formed by a jet of atoms of a noble gas, helium. This lens benefits from the high transmission of helium in the XUV spectral range and at the same time can be precisely controlled by changing the density of the gas in the jet. This is important in order to tune the focal length and minimize the spot sizes of the focused XUV beams.

In comparison to curved mirrors that are often used to focus XUV radiation, these gaseous refractive lenses have a number of advantages: A ‘new’ lens is constantly generated through the flow of atoms in the jet, meaning that problems with damages are avoided. Furthermore, a gas lens results in virtually no loss of XUV radiation compared to a typical mirror. “This is a major improvement, because the generation of XUV beams is complex and often very expensive,” Dr. Bernd Schuette, MBI scientist and corresponding author of the publication, explains.

In the work the researchers have further demonstrated that an atomic jet can act as a prism breaking the XUV radiation into its constituent spectral components. This can be compared to the observation of a rainbow, resulting from the breaking of the Sun light into its spectral colors by water droplets, except that the ‘colors’ of the XUV light are not visible to a human eye.

The development of the gas-phase lenses and prisms in the XUV region makes it possible to transfer optical techniques that are based on refraction and that are widely used in the visible and infrared part of the electromagnetic spectrum, to the XUV domain. Gas lenses could e.g. be exploited to develop an XUV microscope or to focus XUV beams to nanometer spot sizes. This may be applied in the future, for instance, to observe structural changes of biomolecules on the shortest timescales.

Story Source:

Materials provided by Forschungsverbund Berlin. Note: Content may be edited for style and length.

[ad_2]