[ad_1]

Researchers from Michigan State University and the RIKEN Nishina Center in Japan discovered eight new rare isotopes of the elements phosphorus, sulfur, chlorine, argon, potassium, scandium and, most importantly, calcium.

These are the heaviest isotopes of these elements ever found.

Isotopes are different forms of elements found in nature. Isotopes of each element contain the same number of protons, but a different number of neutrons. The more neutrons that are added to an element, the “heavier” it is. The heaviest isotope of an element represents the limit of how many neutrons the nucleus can hold. Also, isotopes of the same element have different physical properties. “Stable” isotopes live forever, while some heavy isotopes might only live for a few seconds. Some even heavier ones might barely exist fractions of a second before disintegrating.

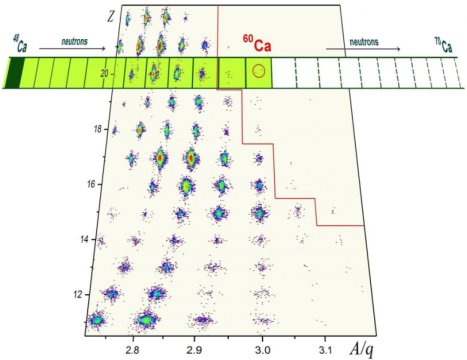

The most interesting short-lived isotopes synthesized during a recent experiment at RIKEN’s Radioactive Isotope Beam Factory (RIBF) were calcium-59 and calcium-60, which are now the most neutron-laden calcium isotopes known to science. The nucleus of calcium-60 has 20 protons and twice as many neutrons. That’s 12 more neutrons than the heaviest of the stable calcium isotopes, calcium-48. This stable isotope disintegrates after living for hundreds of quintillion years, or 40 trillion times the age of the universe. In contrast, calcium-60 lives for a few thousandths of a second.

Oleg Tarasov, a staff physicist at the National Superconducting Cyclotron Laboratory (NSCL) at MSU, is a spokesperson for the experiment.

Tarasov explained that proving the existence of a certain isotope of an element can advance scientists’ understanding of the nuclear force. This is a longstanding quest in nuclear science.

“At the heart of an atom, protons and neutrons are held together by the nuclear force, forming the atomic nucleus,” Tarasov said. “Scientists continue to research what combinations of protons and neutrons can exist in nature even if it is only for fleeting fractions of a second.”

Alexandra Gade, professor of physics at MSU and NSCL chief scientist, is interested in the comparison of the new discoveries to nuclear models. In a way, these models paint a picture of the nucleus at different resolutions.

“Some of these models that describe nuclei at the highest resolution scale predict that 20 protons and 40 neutrons will not hold together to form Ca-60,” Gade said. “The discovery of calcium-60 will prompt theorists to identify missing ingredients in their models.”

Two of the other new isotopes of sulfur and chlorine, S-49 and Cl-52, were not predicted to exist by a number of models that paint a lower resolution picture of nuclei. Their ingredients can now be refined as well.

Creating and identifying rare isotopes is the nuclear-physics version of a formidable needle-in-a-haystack problem. To synthesize these new isotopes, researchers accelerated an intense beam of heavy zinc particles onto a block of beryllium. In the resulting debris of the collision, with a minuscule chance, a rare isotope such as calcium-60 is formed. The intense zinc beam that enabled the discovery of calcium-59 and calcium-60 was provided by the RIBF, which is presently home to the world’s most powerful accelerator facility in the field. The isotopes calcium-57 and 58 were discovered in 2009 at NSCL.

In the future, the Facility for Rare Isotope Beams (FRIB) at Michigan State University will allow scientists might be able to make calcium-68 or even calcium-70, which may be the heaviest calcium isotopes.

[ad_2]