[ad_1]

From photonics to pharmaceuticals, materials made with polymer nanoparticles hold promise for products of the future. However, there are still gaps in understanding the properties of these tiny plastic-like particles.

Now, Hojin Kim, a graduate student in chemical and biomolecular engineering at the University of Delaware, together with a team of collaborating scientists at the Max Planck Institute for Polymer Research in Germany, Princeton University and the University of Trento, has uncovered new insights about polymer nanoparticles. The team’s findings, including properties such as surface mobility, glass transition temperature and elastic modulus, were published in Nature Communications.

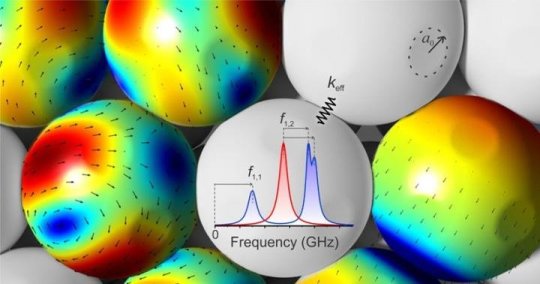

Under the direction of MPI Prof. George Fytas, the team used Brillouin light spectroscopy, a technique that spelunks the molecular properties of microscopic nanoparticles by examining how they vibrate.

“We analyzed the vibration between each nanoparticle to understand how their mechanical properties change at different temperatures,” Kim said. “We asked, ‘What does a vibration at different temperatures indicate? What does it physically mean?’ “

The characteristics of polymer nanoparticles differ from those of larger particles of the same material. “Their nanostructure and small size provide different mechanical properties,” Kim said. “It’s really important to understand the thermal behavior of nanoparticles in order to improve the performance of a material.”

Take polystyrene, a material commonly used in nanotechnology. Larger particles of this material are used in plastic bottles, cups and packaging materials.

“Polymer nanoparticles can be more flexible or weaker at the glass transition temperature at which they soften from a stiff texture to a soft one, and it decreases as particle size decreases,” Kim said. That’s partly because polymer mobility at small particle surface can be activated easily. It’s important to know when and why this transition occurs, since some products, such as filter membranes, need to stay strong when exposed to a variety of conditions.

For example, a disposable plastic cup made with the polymer polystyrene might hold up in boiling water — but that cup doesn’t have nanoparticles. The research team found that polystyrene nanoparticles start to experience the thermal transition at 343 Kelvin (158 degrees F), known as the softening temperature, below a glass transition temperature of 372 K (210 F) of the nanoparticles, just short of the temperature of boiling water. When heated to this point, the nanoparticles don’t vibrate — they stand completely still.

This hadn’t been seen before, and the team found evidence to suggest that this temperature may activate a highly mobile surface layer in the nanoparticle, Kim said. As particles heated up between their softening temperature and glass transition temperature, the particles interacted with each other more and more. Other research groups have previously suspected that glass transition temperature drops with decreases in particle size decreases because of differences in particle mobility, but they could not observe it directly.

“Using different method and instruments, we analyzed our data at different temperatures and actually verified there is something on the polymer nanoparticle surface that is more mobile compared to its core,” he said.

By studying interactions between the nanoparticles, the team also uncovered their elastic modulus, or stiffness.

Next up, Kim plans to use this information to build a nanoparticle film that can govern the propagation of sound waves.

Eric Furst, professor and chair of the Department of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering at UD, is also a corresponding author on the paper.

“Hojin took the lead on this project and achieved results beyond what I could have predicted,” said Furst. “He exemplifies excellence in doctoral engineering research at Delaware, and I can’t wait to see what he does next.”

[ad_2]