[ad_1]

For 15 years, scientists have tried to exploit the “miracle material” graphene to produce nanoscale electronics. On paper, graphene should be great for just that: it is ultra-thin — only one atom thick in fact and therefore two-dimensional, it is excellent for conducting electrical current and should be ideal for future forms of electronics that are faster and more energy efficient. In addition, graphene consists of carbon atoms — of which we have an unlimited supply.

In theory, graphene can be altered to perform many different tasks within e.g. electronics, photonics or sensors simply by drawing tiny patterns in it, as this fundamentally alters its quantum properties. One “simple” task, which has turned out to be surprisingly difficult, is to induce a bandgap — which is crucial for making transistors and optoelectronic devices. However, since graphene is only an atom thick all of the atoms are important and even tiny irregularities in the pattern can destroy its properties.

“Graphene is a fantastic material, which I think will play a crucial role in making new nanoscale electronics. The problem is that it is extremely difficult to engineer the electrical properties,” says Peter Bøggild, a professor at DTU Physics.

The Center for Nanostructured Graphene at DTU and Aalborg University was established in 2012 specifically to study how the properties of graphene can be engineered, for instance by making a very fine pattern of holes. This should subtly change the quantum nature of the electrons in the material, and allow the properties of graphene to be tailored. However, the team of researchers from DTU and Aalborg experienced the same as many other researchers worldwide: it didn’t work.

“When you make patterns in a material like graphene, you do so in order to change its properties in a controlled way — to match your design. However, what we have seen throughout the years is that we can make the holes, but not without introducing so much disorder and contamination that it no longer behaves like graphene. It is a bit similar to making a water pipe, with a poor flow rate because of coarse manufacturing. On the outside, it might look fine. For electronics, that is obviously disastrous,” says Peter Bøggild.

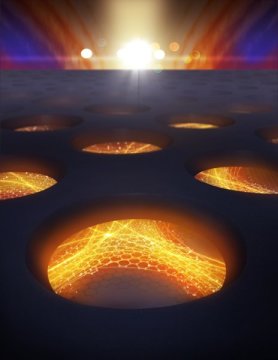

Now, the team of scientists have solved the problem. Two postdocs from DTU Physics, Bjarke Jessen and Lene Gammelgaard, first encapsulated graphene inside another two-dimensional material — hexagonal boron nitride, a non-conductive material that is often used for protecting graphene’s properties.

Next, they used a technique called electron beam lithography to carefully pattern the protective layer of boron nitride and graphene below with a dense array of ultra small holes. The holes have a diameter of approx. 20 nanometers, with just 12 nanometers between them — however, the roughness at the edge of the holes is less than 1 nanometer or a billionth of a meter. This allows 1000 times more electrical current to flow than had been reported in such small graphene structures.

“We have shown that we can control graphene’s band structure and design how it should behave. When we control the band structure, we have access to all of graphene’s properties — and we found to our surprise that some of the most subtle quantum electronic effects survive the dense patterning — that is extremely encouraging. Our work suggests that we can sit in front of the computer and design components and devices — or dream up something entirely new — and then go to the laboratory and realise them in practice,” says Peter Bøggild. He continues:

“Many scientists had long since abandoned attempting nanolithography in graphene on this scale, and it is quite a pity since nanostructuring is a crucial tool for exploiting the most exciting features of graphene electronics and photonics. Now we have figured out how it can be done; one could say that the curse is lifted. There are other challenges, but the fact that we can tailor electronic properties of graphene is a big step towards creating new electronics with extremely small dimensions,” says Peter Bøggild.

Story Source:

Materials provided by Technical University of Denmark. Note: Content may be edited for style and length.

[ad_2]