[ad_1]

Scientists have been able to prove the existence of small black holes and those that are super-massive but the existence of an elusive type of black hole, known as intermediate-mass black holes (IMBHs) is hotly debated. New research coming out of the Space Science Center at the University of New Hampshire shows the strongest evidence to date that this middle-of-the-road black hole exists, by serendipitously capturing one in action devouring an encountering star.

“We feel very lucky to have spotted this object with a significant amount of high quality data, which helps pinpoint the mass of the black hole and understand the nature of this spectacular event,” says Dacheng Lin, a research assistant professor at UNH’s Space Science Center and the study’s lead author. “Earlier research, including our own work, saw similar events, but they were either caught too late or were too far away.”

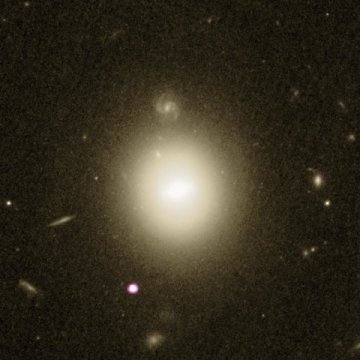

In their study, published in Nature Astronomy, researchers used satellite imaging to detect for the first time this significant telltale sign of activity. They found an enormous multiwavelength radiation flare from the outskirts of a distant galaxy. The brightness of the flare decayed over time exactly as expected by a star disrupting, or being devoured, by the black hole. In this case, the star was disrupted in October 2003 and the radiation it created decayed over the next decade. The distribution of emitted photons over the energy depends on the size of the black hole. This data provides one of the very few robust ways to weight, or determine the size of, the black hole.

Researchers used data from a trio of orbiting X-ray telescopes, NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory and Swift Satellite as well as ESA’s XMM-Newton, to find the multiwavelength radiation flares that helped identify the otherwise uncommon IMBHs. The characteristic of a long flare offers evidence of a star being torn apart and is known as a tidal disruption event (TDE). Tidal forces, due to the intense gravity from the black hole, can destroy an object — such as a star — that wanders too close. During a TDE, some of the stellar debris is flung outward at high speeds, while the rest falls toward the black hole. As it travels inward, and is ingested by the black hole, the material heats up to millions of degrees and generates a distinct X-ray flare. According to the researchers, these types of flares, can easily reach the maximum luminosity and are one of the most effective way to detect IMBHs.

“From the theory of galaxy formation, we expect a lot of wandering intermediate-mass black holes in star clusters,” said Lin. “But there are very, very few that we know of, because they are normally unbelievably quiet and very hard to detect and energy bursts from encountering stars being shredded happen so rarely.”

Because of the very low occurrence rate of such star-triggered outbursts for an IMBH, the scientists believe that their discovery implies that there could be many IMBHs lurking in a dormant state in galaxy peripheries across the local universe.

Story Source:

Materials provided by University of New Hampshire. Note: Content may be edited for style and length.

[ad_2]