Scientists at the University of Richmond report that driving an electric car makes lab rats happy. Being driven around in autonomous vehicles makes them apprehensive. The lesson for humanity is clear, is it not? Drive an electric car and be happy!

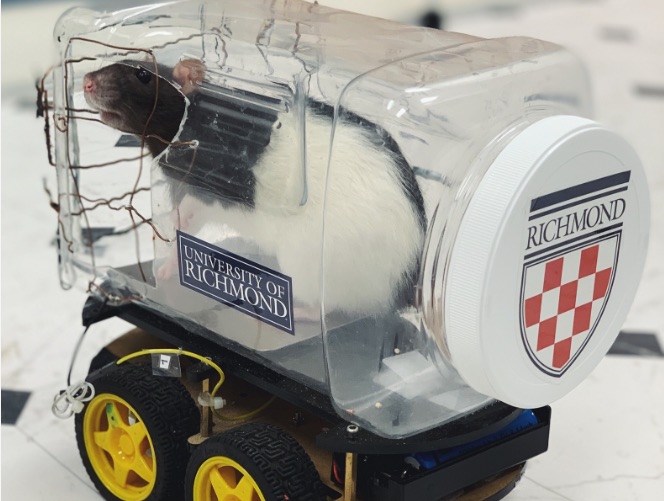

The study involved six female and 11 male rats, who the researchers taught to pilot little cars with aluminium floors and three copper bars serving as a steering mechanisms. When the rats stood on the floors and touched their paws to the copper bars, the vehicles would move accordingly. The training was reinforced with rewards of Froot Loop cereal.

Psychology professor Kelly Lambert, a neuroscientist who led the study, told New Scientist that rats have previously been shown to be able to recognize objects, press bars and find their way around mazes. But she and her colleagues wanted to see whether rats were able to learn the more sophisticated task of operating a moving vehicle.

‘They learned to navigate the car in unique ways and engaged in steering patterns they had never used to eventually arrive at the reward,” Lambert told the publication.

Lest you think this is merely a stunt destined for the late-night TV talk show circuit, there is an important finding here: Learning to drive seemed to have a relaxing effect on the vermin, as measured by their levels of corticosterone, a hormone that spikes in stressful situations, and dehydroepiandrosterone, which counteracts stress. The ratio of the two hormones was flipped in the rats and increased the more they drove.

The rats that lived in a complex and stimulating environment learned how to drive much faster than the rats who lived in a dreary laboratory, Lambert told Business Insider.

Lambert has apparently done previous work that found that rats experience a reduction in stress after they master difficult tasks, like digging up buried food, suggesting they may experience the same kind of satisfaction people feel after perfecting a new skill. The team also found that the rats that drove themselves were less stressed than rats that were driven around as passengers in remote-controlled cars.

The practical takeaway from all of this is that scientists could substitute driving tests like this one for more traditional maze tests to study things like the effects of Parkinson’s disease on motor skills and spatial awareness.

Next up are follow-up experiments to try and understand how rats learn to drive and why it seems to reduce stress. We can’t help but wonder whether that might include introducing the scourge known as traffic to the equation.