Typhoid fever infects up to 20 million people annually, killing as many as 161,000, and has many drug-resistant strains. Jeongmin Song, assistant professor of microbiology and immunology in the College of Veterinary Medicine, has discovered a new potential defense against this bacterial disease: one of its closest relatives.

Song studies salmonella Typhi, the bacteria that cause typhoid fever, and how it invades and infects host cells. In a study published May 11 in Cell Host & Microbe, Song and her team discovered that typhoid’s close cousin, salmonella Javiana, invades and infects hosts cells in almost the same way, but with much less harmful results.

“We found that one of the important differences in deadliness between these two bacteria came down to a handful tiny molecular changes which dictate what host cells they attack,” Song said. This family resemblance, she said, could potentially be leveraged as a potential vaccine against typhoid fever.

In previous studies, Song discovered that salmonella Typhi produces a toxin that is responsible for most of the symptoms of typhoid fever. The toxin does the heavy lifting in the disease process, using specific proteins and a one-two technique when attacking its prey, white blood cells.

First, toxin protein “B” zeroes in on specific sugars adorning the outer membrane of immune cells, helping the toxin find its victim. Then, two toxin “A” proteins enter the cell and disrupt the white blood cells’ immune response. The bacteria’s special method of binding its toxin to immune cells is the “secret key” behind its deadliness, Song explains.

Song knew that salmonella Javiana had the same type of search-and-destroy proteins in its molecular toolkit, but only causes short-lived food poisoning. “Surprisingly,” she said, “we found that two toxins play different roles despite their high similarity.”

Indeed, Javiana toxins differ from typhoid toxins by only six amino acids. The researchers found that those tiny differences were, in fact, the critical reason why typhoid bacteria can be deadly, while Javiana just cause a sick stomach.

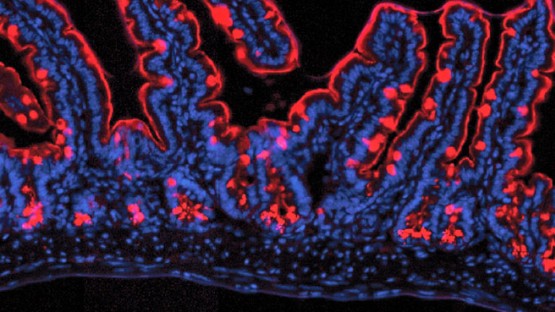

The researchers discovered that both toxins had three binding sites, but the difference in their amino acid makeup enabled typhoid toxins to attack a broader range of cellular targets and induce deadly systemic infections throughout the body, while Javiana could only attach to cells in the intestinal tract.

Song and her team also wondered if the similarity could also be a form of security. “We wondered if exposure to Javiana bacteria or their toxin might provide some protection against typhoid-related illnesses,” she said.

The team exposed mice first to Javiana toxins, then to a lethal dose of typhoid toxins. They found that the Javiana exposure protected the mice from fatal typhoid infection.

“This finding,” Song said, “may be the key to designing improved typhoid fever vaccines and therapeutics.”

Co-lead authors are Sohyoung Lee, research associate in the Song lab, and Yi-An Yang, former postdoctoral researcher in the Song Lab. Other contributors came from CVM and from the Scripps Research Institute of La Jolla, California.

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health, the Mizutani Foundation for Glycoscience, the National Cancer Institute and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences.

Lauren Cahoon Roberts is assistant director of communications at the College of Veterinary Medicine.