New research shows that crustaceans such as shrimps, lobsters and crabs have more in common with their insect relatives than previously thought — when it comes to the structure of their brains.

Both insects and crustaceans possess mushroom-shaped brain structures known in insects to be required for learning, memory and possibly negotiating complex, three-dimensional environments, according to the study, led by University of Arizona neuroscientist Nicholas Strausfeld.

The research, published in the open-access journal eLife, challenges a widely held belief in the scientific community that these brain structures — called “mushroom bodies” — are conspicuously absent from crustacean brains.

In 2017, Strausfeld’s team reported a detailed analysis of mushroom bodies discovered in the brain of the mantis shrimp, Squilla mantis. In the current paper, the group provides evidence that neuro-anatomical features that define mushroom bodies — at one time thought to be an evolutionary feature proprietary to insects — are present across crustaceans, a group that includes more than 50,000 species.

Crustaceans and insects are known to descend from a common ancestor that lived about a half billion years ago and has long been extinct.

“The mushroom body is an incredibly ancient, fundamental brain structure,” said Strausfeld, Regents Professor of neuroscience and director of the University of Arizona’s Center for Insect Science. “When you look across the arthropods as a group, it’s everywhere.”

In addition to insects and crustaceans, other arthropods include arachnids, such as scorpions and spiders, and myriapods, such as millipedes and centipedes.

Characterized by their external skeletons and jointed appendages, arthropods make up the most species-rich group of animals known, populating almost every conceivable habitat. About 480 million years ago, the arthropod family tree split, with one lineage producing the arachnids and another the mandibulates. The second group split again to provide the lineage leading to modern crustaceans, including shrimps and lobsters, and six-legged creatures, including insects — the most diverse group of arthropods living today.

Decades of research has untangled arthropods’ evolutionary relationships using morphological, molecular and genetic data, as well as evidence from the structure of their brains.

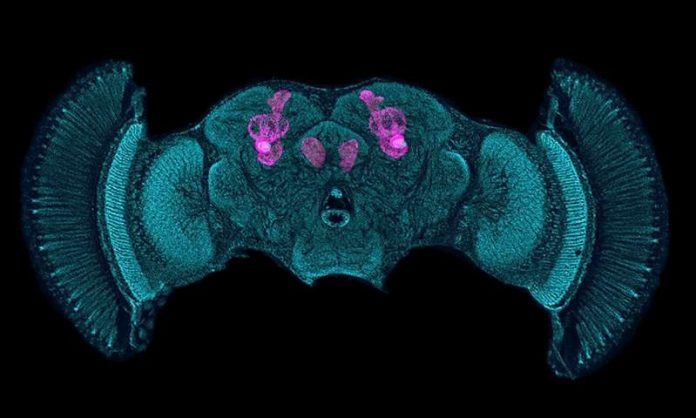

Mushroom bodies in the brain have been shown to be the central processing units where sensory input converges. Vision, smell, taste and touch all are integrated here, as studies on honeybees have shown. Arranged in pairs, each mushroom body consists of a column-like portion, called the lobe, capped by a dome-like structure, called the calyx, where neurons that relay information sent from the animal’s sensory organs converge. This information is passed to neurons that supply thousands of intersecting nerve fibers in the lobes that are essential for computing and storing memories.

Recent research by other scientists has also shown that those circuits interact with other brain centers in strengthening or reducing the importance of a recollection as the animal gathers experiences from its environment.

“The mushroom bodies contain networks where interesting associations are being made that give rise to memory,” Strausfeld said. “It’s how the animal makes sense of its environment.”

A more evolutionarily “modern” group of crustaceans called Reptantia, which includes many lobsters and crabs, do indeed appear to have brain centers that don’t look at all like the insect mushroom body. This, the authors suggest, helped create the misconception crustaceans lack the structures altogether.

Brain analysis of crustaceans has revealed that while the mushroom bodies found in crustaceans appear more diverse than those of insects, their defining neuroanatomical and molecular elements are all there.

Using crustacean brain samples, the researchers applied tagged antibodies that act like probes, homing in on and highlighting proteins that have been shown to be essential for learning and memory in fruit flies. Sensitive tissue-staining techniques further enabled visualization of mushroom bodies’ intricate architecture.

“We know of several proteins that are necessary for the establishment of learning and memory in fruit flies,” Strausfeld said, “and if you use antibodies that detect those proteins across insect species, the mushroom bodies light up every time.”

Using this method revealed that the same proteins are not unique to insects; they show up in the brains of other arthropods, including centipedes, millipedes and some arachnids. Even vertebrates, including humans, have them in a brain structure called the hippocampus, a known center for memory and learning.

“Corresponding brain centers — the mushroom body in arthropods, marine worms, flatworms and, possibly, the hippocampus of vertebrates — appear to have a very ancient origin in the evolution of animal life,” Strausfeld said.

So why do the most commonly studied crustaceans have mushroom bodies that can appear so drastically different from their insect counterparts? Strausfeld and his co-authors have a theory: Crustacean species that inhabit environments that demand knowledge about elaborate, three-dimensional areas are precisely the ones whose mushroom bodies most closely resemble those in insects, a group that has also mastered the three-dimensional world by evolving to fly.

“We don’t think that’s a coincidence,” Strausfeld says. “We propose that that the complexity of inhabiting a three-dimensional world may demand special neural networks that allow a sophisticated level of cognition for negotiating that space in three dimensions.”

Lobsters and crabs, on the other hand, spend their lives confined mostly to the seafloor, which may explain why they’ve historically been said to lack mushroom bodies.

“At the risk of offending colleagues who are partial to crabs and lobsters: I view many of these as flat-world inhabitants,” Strausfeld says. “Future studies will be able to tell us which are smarter: the reef dwelling mantis shrimp, a top predator, or the reclusive lobster.”

Strausfeld co-authored the paper with two of his former students — Gabriella Wolff, now a post-doctoral fellow at the University of Washington, and Marcel Sayre, now a doctoral student at Lund University in Sweden. They hope that the study of mushroom bodies will further help in resolving how brains may have evolved and what environmental conditions shaped that process.

“This research moves us closer to answering the ultimate question,” Strausfeld says. “We want to know: What was the earliest brain like?”