Last year, MIT engineers developed a double-sided adhesive that could quickly and firmly stick to wet surfaces such as biological tissues. They showed that the tape could be used to seal up rips and tears in lungs and intestines within seconds, or to affix implants and other medical devices to the surfaces of organs such as the heart.

Now they have further developed their adhesive so that it can be detached from the underlying tissue without causing any damage. By applying a liquid solution, the new version can be peeled away like a slippery gel in case it needs to be adjusted during surgery, for example, or removed once the tissue has healed.

“This is like a painless Band-Aid for internal organs,” says Xuanhe Zhao, professor of mechanical engineering and of civil and environmental engineering at MIT. “You put the adhesive on, and if for any reason you want to take it off, you can do so on-demand, without pain.”

The team’s new design is detailed in a paper published today in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. Zhao’s co-authors are first authors Xiaoyu Chen and Hyunwoo Yuk along with Jingjing Wu at MIT, and Christoph Nabzdyk at Mayo Clinic Rochester.

Unbreakable bonds

In considering designs for their original adhesive, the researchers quickly realized that it is extremely difficult for tape to stick to wet surfaces, as the thin layer of water lubricates and prevents most adhesives from taking hold.

To get around a tissue’s natural slipperiness, the team designed their original adhesive out of biocompatible polymers including polyacrylic acid, a highly absorbent material commonly used in diapers and pharmaceuticals, that soaks up water, then quickly forms weak hydrogen bonds with the tissue’s surface. To reinforce these bonds, the researchers embedded the material with NHS esters, chemical groups that form stronger, longer-lasting bonds with proteins on a tissue’s surface.

While these chemical bonds gave the tape its ultrastrong grip, they were also difficult to break, and the team found that detaching the tape from tissue was a messy, potentially harmful task.

“Removing the tape could potentially create more of an inflammatory response in tissue, and prolong healing,” Yuk says. “It’s a real practical problem.”

Scotch tape for surgeons

To make the adhesive detachable, the team first tweaked the adhesive itself. To the original material, they added a new disulfide linker molecule, which can be placed between covalent bonds with a tissue’s surface proteins. The team chose to synthesize this particular molecule because its bonds, while strong, can be easily severed if exposed to a particular reducing agent.

The researchers then looked through the literature to identify a suitable reducing agent that was both biocompatible and able to sever the necessary bonds within the adhesive. They found that glutathione, an antioxidant naturally found in most cells, was able to break long-lasting covalent bonds such as disulfide, while sodium bicarbonate, also known as baking soda, could deactivate the adhesive’s shorter-lasting hydrogen bonds.

The team mixed concentrations of glutathione and sodium bicarbonate together in a saline solution, and sprayed the solution over samples of adhesive that they placed over various organ and tissue specimens, including pig heart, lung, and intestines. In all their tests, regardless of how long the adhesive had been applied to the tissue, the researchers found that, once they sprayed the triggering solution onto the tape, they were able to peel the tape away from the tissue within about five minutes, without causing tissue damage.

Detaching tissue bandaid from the hydrogel after applying the triggering solution for 5 min. The adhesive can be easily peeled off without causing damage to the underlying hydrogel. Courtesy of the researchers.

“That’s about the time it takes for the solution to diffuse through the tape to the surface where the tape meets the tissue,” Chen says. “At that point, the solution converts this extremely sticky adhesive to just a layer of slippery gel that you can easily peel off.”

The researchers also fabricated a version of the adhesive that they etched with tiny channels the solution can also diffuse through. This design should be particularly useful if the tape were used to attach implants and other medical devices. In this case, spraying solution on the tape’s surface would not be an option. Instead, a surgeon could apply the solution around the tape’s edges, where it could diffuse through the adhesive’s channels.

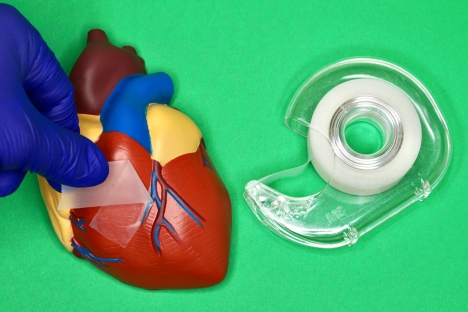

“Our hope is that some day, operating rooms can have dispensers of these adhesives, alongside bottles of triggering solution,” Yuk says. “Surgeons can use this like Scotch tape, applying, detaching, and reapplying it on demand.”

The team is working with Nabzdyk and other surgeons to see whether the new adhesive can help repair conditions such as hemorrhages and leaky intestines.

“Our goal is to use bioadhesive technologies to replace sutures, which is a thousands-of-years-old wound closure technology without too much innovation,” Zhao says. “Now we think we have a way to make the next innovation for wound closure.”

This research was funded, in part, by the National Science Foundation and MIT’s Deshpande Center for Technological Innovation.