Researchers working on the next frontier of weather forecasting are hoping that weather conditions 3-to-4 weeks out will soon be as readily available as seven-day forecasts. Having this type of weather information–called subseasonal forecasts–in the hands of the public and emergency managers can provide the critical lead time necessary to prepare for natural hazards like heat waves or the next polar vortex.

Scientists like University of Miami (UM) Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science Professor Ben Kirtman and Assistant Professor Kathleen Pegion at George Mason University are leading the way to close this critical gap in the weather forecast system through the SubX project. SubX–short for The Subseasonal Experiment–is a research-to-operations project to provide better subseasonal forecasts to the National Weather Service.

“Subseasonal predictions is the most difficult timeframe to predict,” said Kirtman, a professor of atmospheric sciences and director of the NOAA Cooperative Institute for Marine and Atmospheric Studies (CIMAS). “The hardest part is taking all the observations and putting them into the model.”

SubX is filling the gap between the prediction of weather and the prediction of seasonal conditions, which is guided by slowly evolving ocean conditions like sea surface temperatures and soil moisture and variability in the climate system that work on time scales of weeks. To get to the subseasonal scale, scientists need information on conditions that affects global weather such as large-scale convective anomalies like the Madden-Julian Oscillation in the tropical Indian Ocean into their computer models.

“The SubX public database makes 3-4 week forecasts available right now and provides researchers the data infrastructure to investigate how to make them even better in the future,” said Pegion.

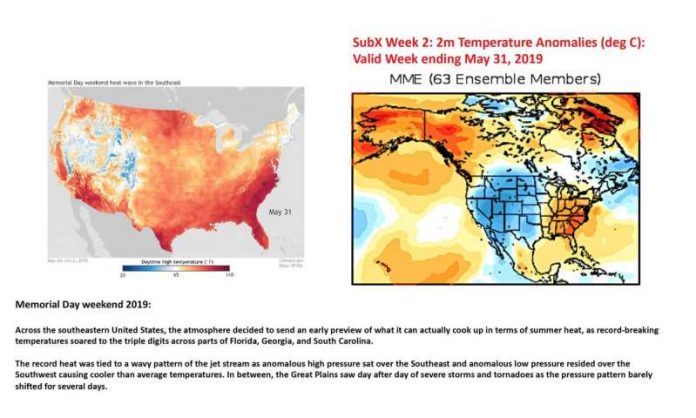

SubX has already shown great promise forecasting weather conditions. It accurately predicted the amount of rainfall from Hurricane Michael—roughly 50 mm, the 4th of July heat wave in Alaska where temperatures reached over 90 degrees Fahrenheit–20 to 30 degrees above average in some locations –and the polar vortex that hit the midwestern U.S. and eastern Canada in late January and killed 22 people.

For Kirtman and his team, the power to make these predictions requires the capacity to compute and store a large amount of data. This means they depend heavily on the UM Center for Computational Science’s (CCS) computing capability to handle the complex computation needed for their models. CCS resources are critical for Kirtman and Pegion to meet the on-time, in-real-time, all-the-time deadlines required for SubX to be successful.

SubX’s publicly available database contains 17 years of historical reforecasts (1999-2015) and more than 18 months of real-time forecasts for use by the research community and the National Weather Service.

As Kirtman and his research team pointed out in an Oct. 2019 article in the American Meteorological Society’s journal BAMS, “early warning of heat waves, extreme cold, flooding rains, flash drought, or other weather hazards as far as 4 weeks into the future could allow for risk reduction and disaster preparedness, potentially preserving life and resources. Less extreme, but no less important, reliable probabilistic forecasts about the potential for warmer, colder, wetter, or drier conditions at a few weeks lead are valuable for routine planning and resource management.”