New study shows that the ocean currents are somewhere controlled by the smallest sea creatures. Creatures like shrimp and Krill might be able to control the turbulence in the ocean.

Crashing waves aren’t the only tumultuous parts of the sea. Far beneath any ocean’s surface, immensely heavy layers of water are constantly turning over, like the icy contents of 7-Eleven Slurpee machine. Like slushy drinks, stirring around the nutrients in ocean waters is extremely important to the life that depends on them, but the engines that drive the turnover in the water are completely natural ones. And, as a new study in Nature indicates, many of them are not what you’d expect.

In a paper published in Nature on Wednesday, researchers at Stanford University put the spotlight on a very unlikely source of ocean water mixing: tiny crustaceans, slightly smaller than a dime, that actually have a significant effect on the mixing of ocean waters. Previous studies have suggested that these tiny animals couldn’t have an effect much larger than their 15-millimeter-long bodies, but the researchers demonstrate that there’s strength in numbers. They write that huge masses of brine shrimp (Artemia salina), hundreds of feet long, could contribute meaningfully to ocean water mixing. Sure, one little ant kicking its legs probably couldn’t stir a bowl of cake batter, but what about hundreds — or even billions — of ants?

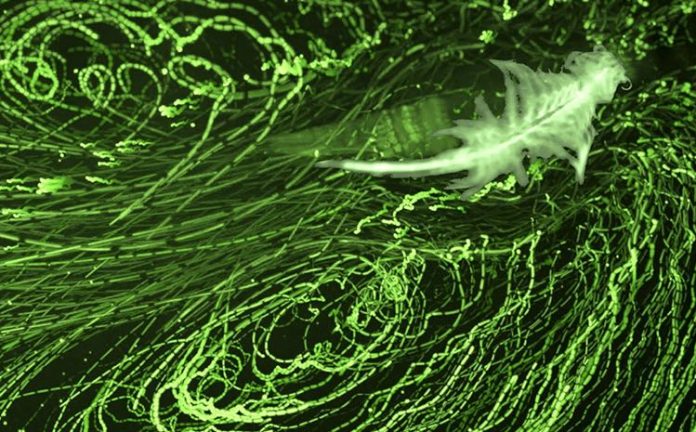

To conduct the study, first-authored by Isabel Houghton, a Ph.D. student in the fluid mechanics lab of Stanford engineer John Dabiri, Ph.D., researchers used LED lights to simulate daylight, triggering the daily migration of captive brine shrimp toward the surface of water within a clear cylinder. In the process, the brine shrimp swam through two separate layers of water, one much saltier than the other, mimicking ocean conditions. Using sensitive cameras to observe the effect the tiny animals had on the two layers of water, the team made observations that could up-end conventional wisdom about ocean mixing.

“Ocean dynamics are directly connected to global climate through interactions with the atmosphere,” said Dabiri in a statement published on Wednesday. “The fact that swimming animals could play a significant role in ocean mixing — an idea that has been almost heretical in oceanography — could therefore have consequences far beyond the immediate waters where the animals reside.” Once the animals passed between layers, they brought water with them, mixing it past the point where it could settle back out into separate layers.

This study is just a first step toward identifying zooplankton’s role in mixing ocean waters. The lab conditions simulate the real-world water column, but on a very small scale, so the researchers’ next step will be to identify parts of the ocean where they can conduct a larger study.

These tiny shrimp might not seem like much, but, just as Will and Bill the krill in Happy Feet 2 gathered all their buddies together to help break the ice, so too could these centimeter-long brine shrimp help mix up the ocean.