Astronaut Scott Kelly’s DNA was altered by a year in space, results from NASA’s Twins Study have confirmed. Seven percent of his genes did not return to normal after he landed, researchers found.

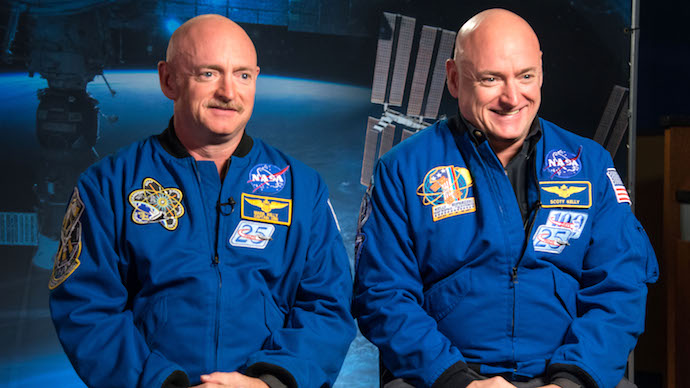

Scott Kelly and his twin brother, Mark Kelly—also an astronaut—were the subjects of the study that sought to find out exactly what happens to the body after a year in space.

Scott stayed on the International Space Station from March 2015 to March 2016, while Mark remained on Earth. This was the final mission for Scott, who spent a total of 520 days in space during his career.

Scott Kelly’s one-year stint in space is “a stepping stone to a three-year mission to Mars,” NASA reported. At present, astronauts only spend six months on the International Space Station as standard. A mission to Mars, however, could take three years.

Researchers studied Scott in space psychologically and physiologically, comparing his results to those of his Earthbound brother. They looked at various proteins and evaluated the twins’ cognition as part of the overall study. Ten research teams presented their preliminary findings last year at NASA’s Human Research Program 2017 Investigators’ Workshop (IWS). The recent 2018 IWS saw these findings confirmed. Researchers also presented data from Scott’s time back on Earth.

The researchers linked space travel to oxygen deprivation stress, increased inflammation and striking nutrient shifts that affect gene expression. Some of these changes went back to normal within hours of landing on Earth. A few, however, still affected Scott six months after his return.

In 2017, researchers discovered that the endcaps of Scott Kelly’s chromosomes—his telomeres—had become longer while he was in space. Further testing confirmed this change, and revealed that most of the telomeres had shortened again within just two days of his return.

After landing, 93 percent of Scott Kelly’s genes returned to normal, the researchers found. The altered 7 percent, however, could indicate long-term changes in genes connected to the immune system, DNA repair, bone formation networks, oxygen deprivation and elevated carbon dioxide levels.

The individual studies on the twins will be combined into a summary paper, as detailed in the graphic above. This summary is set to be released later this year. The research will inform NASA’s understanding of the human body in space for “years to come,” the agency reported, as it “continues to prioritize the health and safety of astronauts on spaceflight missions.”