It is well known that washing clothes can release a large number of microfibers into wastewater, but it is unclear whether drying of clothes would have any impact on the environment. A pilot study by scientists from City University of Hong Kong (CityU) reports that a single clothes dryer can discharge up to 120 million microfibres annually — 1.4 to 40 times of that from washing machines. To control the release of these harmful airborne microfibres, the team suggested that additional filtration systems should be installed for dryer vents as soon as possible.

Dr Zhang Kai, former Research Associate of the State Key Laboratory of Marine Pollution (SKLMP) in CityU and Professor Leung Mei-yee, Director of SKLMP and Chair Professor at Department of Chemistry in CityU co-led the research team. The work was published in the academic journal Environmental Science & Technology Letters, under the title of “Microfibers released into the air from a household tumble dryer”.

Microfibre air pollution deserves attention

Microplastics are a growing threat to aquatic organisms and their ecosystems. Apart from marine and freshwater environments, microfibres have been found in air and terrestrial ecosystems. Exposure to airborne microplastics has been linked to adverse effects on human health, including chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Synthetic textile fibres, such as polyester fibres, are widely used in clothing. But most of the published research has focused on the generation of microfibers from washing machines, and studies about the release of textile-associated microfibers into the atmosphere are little. So, Dr Zhang, Professor Leung and their research team carried out experiments to find out the answer.

Tumble dryers causing microfibre air pollution

In their study, CityU researchers verified the hypothesis that household tumble driers release a large quantity of plastic microfibres, being one of the main sources of microfibre pollution in the atmosphere.

In their experiment, the researchers separately dried clothing items made of polyester and cotton in a tumble dryer that had a vent pipe to the outdoors. As the machine ran for 15 minutes, they collected and counted the airborne particles that exited the vent. The results showed that both types of clothing produced microfibres, which the team suggested comes from the friction of clothes rubbing together as they tumbled around.

They found that the dryer released up to 561,810 microfibres during 15 minutes of use. For both fabrics, the dryer released between 1.4 and 40 times more microscopic fragments than washing machines recorded in previous studies for the same amount of clothing. The release of polyester microfibres increased with the increasing weight of clothes in the dryer, but the release of cotton microfibers remains constant regardless of the weight.

The research team estimated that on average between 90 and 120 million microfibres are produced and released into the outdoor air in a Canadian household’s dryer every year.

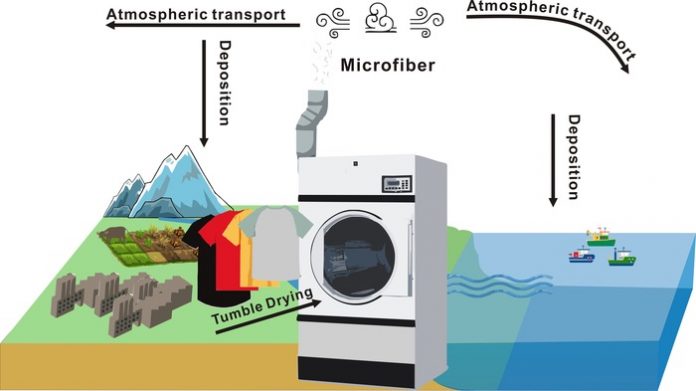

The release of a large quantity of microfibres from synthetic fabrics in tumble dryers into the atmosphere is a concern because they can be irritating if being ingested or inhaled, and can be transported long distances by wind. Also, they can adsorb and transport pollutants for long distances.

Filtration devices should be installed to tumble dryers

Previous studies have shown that although microfibers are released from clothes washers into laundry water, but such wastewater is often treated, removing some or most of the fibres before discharging into rivers, streams or coastal waters. However, air from dryers usually passes through a simple lint filter and a duct before being vented directly to the outdoors.

To alleviate the air pollution caused by microfibres, the team suggested it is essential to minimise the release of microfibres from tumble driers by every possible means. “In the long run, it is essential to make better textiles that is more wear-resistant, more durable, and with enhanced environmental friendliness. But before the realisation of better replacements for synthetic fibres such as polyester, we can minimise the release of microfibres from tumble dryers by installing a simple, engineered filtration devices at the end of the emission pipelines,” Dr Zhang recommended.

By using 3D printing, CityU’s scientists have already designed innovative filters that prevent microplastics from being dispersed from washing machines, and are in the process of designing a similar system for tumble dryers. “To control the release of these airborne microfibres, improved lint filters with smaller mesh size and an additional filtration system should be adapted for dryer vents,” Professor Leung added.