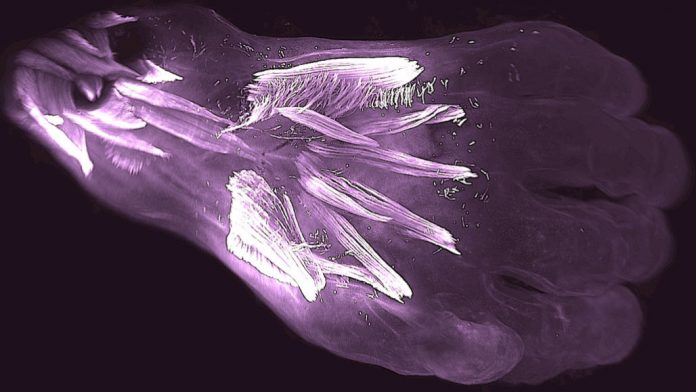

Human embryos are more muscle-bound than adult humans, new microscope images cataloging early development show.

Special immunostaining techniques carried out by researchers from Washington’s Howard University and Sorbonne University in Paris have revealed new human atavisms – remnants of anatomy that evolution never completely ditched – which help to explain how our bodies evolved.

“It used to be that we had more understanding of the early development of fishes, frogs, chicken and mice than in our own species, but these new techniques allow us to see human development in much greater detail,” said Dr Rui Diogo, from Howard University, in a statement. “What is fascinating is that we observed various muscles that have never been described in human prenatal development, and that some of these atavistic muscles were seen even in 11.5-week-old fetuses, which is strikingly late for developmental atavisms.”

The team were able to capture a detailed timetable of the appearance of these muscles, as well as their splitting, fusion, or loss during the growth and development of the embryo. The muscles that fused are called atavistic limb muscles, formed during early human development and then gone prior to our shrieking entrance into the world. It provides an interesting view on evolution – we often see ourselves as becoming progressively more complex, but some anatomical features streamline and become more simple.

“It is in fact instead a story of anatomical simplification,” says Rui Diogo “Mainly muscles are lost, bones are lost.. an adult human has in fact less muscles and bones in the body, in total, than an adult mice, or an adult lizard.”

“Interestingly, some of the atavistic muscles are found on rare occasions in adults, either as anatomical variations without any noticeable effect for the healthy individual, or as the result of congenital malformations,” added Diogo, who is lead author of the study published in the journal Development.

One example of an atavistic muscle found in adults is opponens digiti minimi of the foot. It is present in apes, helping them move their feet with a moble, precise big toe. Humans lost such a digit in evolution, but it’s present in embryos and, on rare occasions, as an anomaly in humans.

“This reinforces the idea that both muscle variations and pathologies can be related to delayed or arrested embryonic development, in this case perhaps a delay or decrease of muscle apoptosis, and helps to explain why these muscles are occasionally found in adult people. It provides a fascinating, powerful example of evolution at play.”

They also found “a striking difference” in the order of muscle development in the arms versus legs, suggesting the similarity is derived. “It means that what most people assume, that the similarities between the upper limb and lower limb are due to an ancestral similarity of these two regions of the body, is likely not true: the similarity of the upper and lower limbs actually became more prominent during the evolution of these limbs, than it was in the first fish with pectoral and pelvic fins, from which the upper and lower limbs arose, respectively.”

This research was published in Development.