The New Scientist reported on Tuesday that researchers at the University of California at Berkeley have created what are, in effect, microscopic, beating hearts from human stem cells. These “hearts” are half a millimeter in diameter and have a single chamber or ventricle. But the newly grown organs beat just like the larger hearts that circulate blood in most higher animals, including human beings. Moreover, the microscopic hearts were grown without recourse to building scaffolds made from donor hearts as previous stem cell grown organs have been created.

The feat has implications ranging from things like testing drugs to the ultimate goal of growing full sized hearts that are suitable for transplant. The method for growing the micro hearts used chemistry as much as engineering.

“Researchers normally use growth factors alone to persuade such stem cells to form the specialised cells of an organ, but Ma’s team used an extra trick. To mimic the physical forces that usually tell fetal stem cells where they can or can’t grow, they etched chemical “no-go” zones, creating wells in the dish. These forced the stem cells to collect in the right configuration.

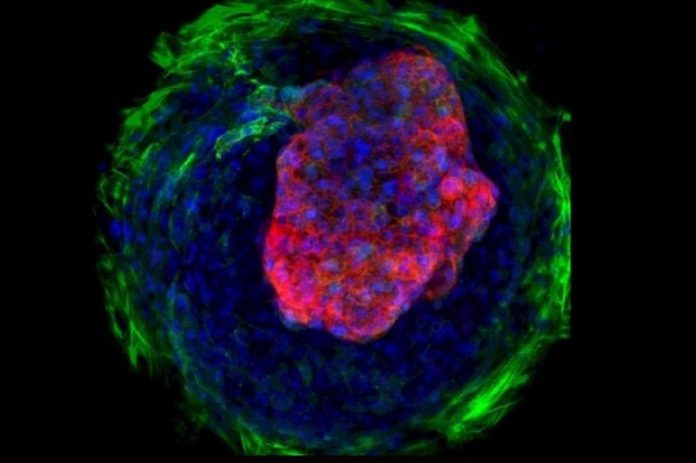

“This process changed their shape, imitating what happens when real hearts form in developing embryos. As a result, those in the centre of the wells turned into beating heart cells called cardiomyocytes. These were surrounded by skin-like cells called fibroblasts, which form the heart’s connective tissue. Most strikingly, the cardiomyocytes also grew upwards to form dome-like cavities that resembled microscopic ventricles.”

Live Science notes that the micro hearts could be used to test drugs in order to assure that they don’t have crippling side effects, such as was the case with thalidomide, a drug given to pregnant women to treat morning sickness. Testing drugs on human tissue could help researchers bypass animal studies, shortening the development and approval time as well as yielding more accurate data.

Further down the road, heart tissue grown in a lab could help repair hearts that have been damaged due to heart attacks. In effect, such hearts could be made as good as new, substituting scar tissue with the healthy heart muscle.

The ultimate goal is the development of full sized, transplantable hearts that are an exact genetic match for the recipient. Ever since the first heart transplants were performed in the late 1960s, patients in need of a new heart had to wait on a donor list to qualify for a new heart. When and if a new heart became available, they have had to take powerful antirejection drugs for the rest of their lives.

In the future, a heart transplant patient will have a new heart, as new and as healthy as that of a newborn child’s, custom made. Once the new heart is implanted, the patient can go on his or her way, like a car with a brand new engine. The implications for human health and well-being are almost incalculable.