With exoplanets now being discovered by the thousands, and estimated to be in the billions in our galaxy alone, attention is naturally turning to how astronomers might be able to search for evidence of life on any of those far-away worlds. Now, a team of scientists is taking a novel approach to doing just that, by creating a colorful catalog of reflection signatures of various life forms on Earth. The new database and research was just published in the March 16 Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

From the abstract:

“Our database covers the visible and near-infrared to the short-wavelength infrared (0.35–2.5 µm) portions of the electromagnetic spectrum and is made freely available from biosignatures.astro.cornell.edu. Our results show how the reflectance properties are dominated by the absorption of light by pigments in the visible portion and by strong absorptions by the cellular water of hydration in the infrared (up to 2.5 µm) portion of the spectrum. Our spectral library provides a broader and more realistic guide based on Earth life for the search for surface features of extraterrestrial life. The library, when used as inputs for modeling disk-integrated spectra of exoplanets, in preparation for the next generation of space-and ground-based instruments, will increase the chances of detecting life.”

“This database gives us the first glimpse at what diverse worlds out there could look like. We looked at a broad set of life-forms, including some from the most extreme parts of Earth,” said Lisa Kaltenegger, professor of astronomy and director of Cornell University’s new Institute for Pale Blue Dots.

“Much of the history of life on Earth has been dominated by microbial life,” as noted in the paper. “It is likely that life on exoplanets evolves through single-celled stages prior to multicellular creatures. Here, we present the first database for a diverse range of life – including extremophiles (organisms living in extreme conditions) found in the most inhospitable environments on Earth – for such surface features in preparation for the next generation of telescopes that will search for a wide variety of life on exoplanets.”

The new database is free to use by other researchers.

The interdisciplinary research team also includes lead author and astronomer Siddharth Hegde of the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy and biologists Ivan G. Paulino-Lima, Ryan Kent, and Lynn Rothschild, all from NASA Ames Research Center. The PNAS article is titled “Surface Biosignatures of Exo-Earths: Remote Detection of Extraterrestrial Life.”

Basically, scientists can measure and analyze the light coming off of the surface of an exoplanet. As known on Earth, various types of life, largely microscopic, give off distinct spectral signatures. The makeup of putative extraterrestrial life forms could be determined by studying the color(s) of their pigmentation.

“On Earth these are just niche environments, but on other worlds, these life-forms might just have the right make to dominate, and now we have a database to know how we could spot that,” said Kaltenegger.

There are currently cultures of 137 different cellular life forms in the database, ranging from Bacillus gathered at the Sonoran Desert to Halorubrum chaoviator found at Baja California, Mexico, to Oocystis minuta, obtained in an oyster pond at Martha’s Vineyard.

“Our results show the amazing diversity of life that one can detect remotely on exoplanets,” said Hegde. “We explore for the first time the reflection signatures of a diversity of pigmented microorganisms isolated from various environments on Earth – including extreme ones – which will provide a more broad guide, based on Earth life, for the search for surface features of extraterrestrial life.”

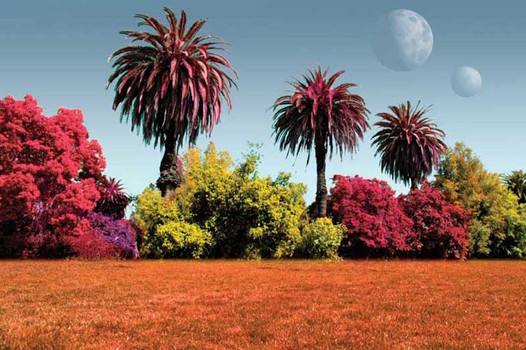

Previous NASA studies have shown that alien planet life could come in a variety of colors, not just the predominantly green that we are familiar with on Earth.

“We can identify the strongest candidate wavelengths of light for the dominant color of photosynthesis on another planet,” said Nancy Kiang, lead author of the study and a biometeorologist at NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies, New York.

“This work broadens our understanding of how life may be detected on Earth-like planets around other stars, while simultaneously improving our understanding of life on Earth,” said Carl Pilcher, director of the NAI at NASA Ames. “This approach – studying Earth life to guide our search for life on other worlds – is the essence of astrobiology.”

Depending on the type of light coming from a host star and the chemistry of a planet’s atmosphere, the coloring of plant life on other worlds may vary greatly. On Earth, most plants appear green because they absorb more blue and red light from the Sun, but less green light.

“It makes one appreciate how life on Earth is so intimately adapted to the special qualities of our home planet and Sun,” said Kiang.

“This work will help guide designs for future space telescopes that will study extrasolar planets, to see if they are habitable, and could have alien plants,” said Victoria Meadows, an astronomer who heads the Virtual Planet Laboratory (VPL).

Despite the vast distances to other planetary systems, techniques such as these – using something as basic and fundamental as color – may help astronomers to find the first evidence for life on other worlds outside of our Solar System.