[ad_1]

Move over, cyanobacteria! A large-scale study of the Earth’s surface ocean indicates the microbes responsible for fixing nitrogen there — previously thought to be almost exclusively photosynthetic cyanobacteria-include an abundant and widely distributed suite of non-photosynthetic bacterial populations.

The international study, published this week in Nature Microbiology, was led by A. Murat Eren (Meren) of the University of Chicago and the Marine Biological Laboratory (MBL), Woods Hole, and Tom O. Delmont of the University of Chicago.

Nitrogen fixation is a critical ecological process in which atmospheric nitrogen is converted to ammonia, making nitrogen “bioavailable” to living organisms to use as a fundamental building block of DNA, RNA and proteins.

“Microbes that can fix nitrogen or carbon are at the center of the ecology of microbial communities in many environments, including the surface ocean,” Delmont says. “Prior to our study, it was thought that the marine microbes responsible for carbon fixation were also largely responsible for fixing nitrogen. It turns out not to be so simple.”

“The ability of microbes to fix nitrogen is vital to all life,” says David Mark Welch, MBL Director of Research. “This study expands our understanding of the biological diversity of nitrogen fixation by providing the first genomic evidence that non-photosynthetic bacteria on the ocean surface can carry out these reactions.”

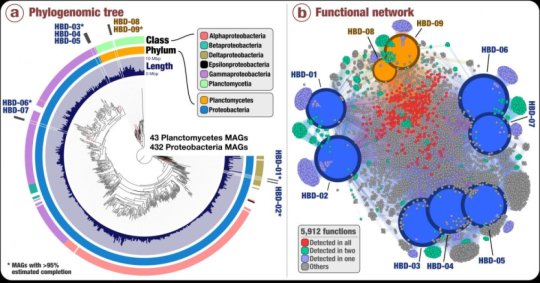

Using anvi’o, a state-of-the-art, open-source bioinformatics platform to analyze metagenomes (the pool of DNA sequences that represent all the microbial organisms found in an environment), the team revealed insights into previously unknown marine microbes with nitrogen fixation capabilities affiliated with Proteobacteria as well as Planctomycetes, a prevalent bacterial phylum that has never been linked to nitrogen fixation before.

These newly described microbial populations occur widely and are particularly abundant in the Pacific Ocean, where they average an estimated 700,000 cells per liter of seawater and up to 3 million cells per liter — orders of magnitude more than previous estimates for non-cyanobacterial nitrogen fixers in the open ocean.

Using data generated from the Tara Oceans expedition from 2009 to 2013, Delmont and colleagues reconstructed about 1,000 microbial genomes from more than 30 billion short metagenomic sequences. Of those 1,000 genomes, nine contained the six genes that are required for nitrogen fixation, and yet lacked the genes needed for photosynthesis. This is the first genomic database of non-photosynthetic microorganisms inhabiting the open ocean and capable of fixing nitrogen.

Because the team reconstructed and used near-complete genomes for their investigation (rather than using a single marker gene for nitrogen fixation), they could resolve the taxonomic affiliations of these nitrogen-fixing populations. They could also investigate their abundance and distribution patterns in the oceans and seas from which the samples came (the Atlantic, Pacific, Indian and Southern oceans and the Mediterranean and Red seas).

“We can now use these population genomes to guide the laboratory cultivation of nitrogen-fixing Planctomycetes and Proteobacteria from the open ocean,” Delmont says. “This will help us understand the conditions in which they fix nitrogen, the complexity of their functional lifestyles, and other aspects of their ecology that we cannot comprehend by just looking at their genomes, genes and inferred functions.”

Meren and Delmont began this research at the Marine Biological Laboratory in 2015 with the support of a University of Chicago Lillie Innovation Award. Meren and his group continue to develop anvi’o, the open-source software platform used in this and other studies investigating the ecology and evolution of microbes through complex environmental sequencing data.

“Environmental metagenomes give us unadulterated access to the complexity of naturally occurring microbial populations,” Meren says. “While our ability to understand them is at the mercy of our molecular technologies and computational tools, it is refreshing to see both advancing rapidly, and there is still so much to discover. We look forward to seeing bench-side advances substantiating these initial insights into environmental populations that likely contribute to one of the most essential biochemical processes that make our planet tick.”

“This study is another example of how resolving genomes directly from the DNA of entire microbial communities is transforming our understanding of microbial diversity,” says co-author Christopher Quince of the University of Warwick, United Kingdom.

[ad_2]