Researchers have been watching the full fallout of a tidal disruption event for years.

If you were to travel some 150 million light years from Earth in the direction of Ursa Major, you’d come across a cataclysmic collision of two galaxies, known collectively as Arp 299. It’s a pretty wild place packed with exploding stars, earning it entry into an elite club of galactic “supernovae factories.”

But rapid self-detonation is not the only way stars die in this highly energetic galactic merger. In a study published on Thursday in Science, an international team of astronomers outline the slow demise of a star twice the size of the Sun as it ran afoul of a supermassive black hole with a mass equal to 20 million Suns.

The pyrotechnic event, which was originally detected in 2005 at the William Herschel Telescope in the Canary Islands, marks the first time that astronomers have had the luxury of observing the full process of a “tidal disruption event” over an extended timeframe. These blowouts occur when stars stray too close to a supermassive black hole, causing them to be ripped apart by the intense gravitational forces of the event horizon.

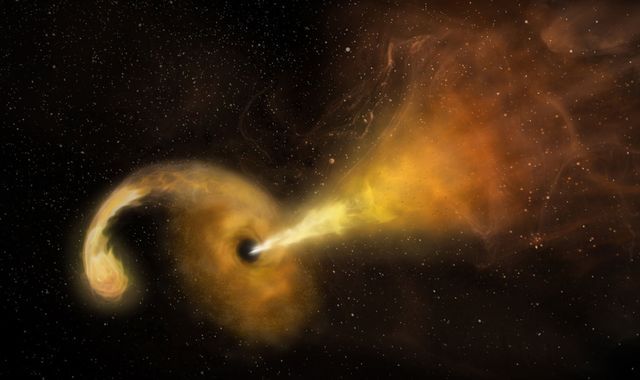

The results sometimes produce “spaghettification” or “stellar pancakes” colorful terms for the way black holes slice-and-dice stars into noodly strings of stellar material. As the tortured star is shredded, its remains create a disc of runoff around the event horizon, some of which is ejected into space in the form of jets traveling at around 25 percent the speed of light. The jets are subject to some of the funky stuff from Albert Einstein’s general theory of relativity—for instance, time slows down for these jets since they’re moving at speeds comparable to light speed.

When just such a jet emerged in 2005, astronomers thought it might be a supernova. But over 10 years of follow-up research from observatories like the National Science Foundation’s Very Long Baseline Array (VLBA) and NASA’s Spitzer Space Telescope, confirmed that it was a jet from a tidal disruption event. This decade-long project is the basis for the new study.

The key giveaway was that the event stayed bright in infrared and radio wavelengths as time wore on, while dimming in the visible and X-ray light spectrum—the expected signature of a black hole chowing down on a star. The research is an example of how long-term surveys of these phenomena can deliver new insights about their formation and evolution.

Though these tidal disruption events are thought to be common, they are rarely detected because of the murky environment surrounding supermassive black holes, where light is obscured by clouds of dust and gas.

“Because of the dust that absorbed any visible light, this particular tidal disruption event may be just the tip of the iceberg of what until now has been a hidden population,” study co-author Seppo Mattila, an astrophysicist at the University of Turku in Finland, said in a statement. “By looking for these events with infrared and radio telescopes, we may be able to discover many more, and learn from them.”