Using data from NASA’s Solar Dynamics Observatory, or SDO, scientists have developed a new model that successfully predicted seven of the Sun’s biggest flares from the last solar cycle, out of a set of nine. With more development, the model could be used to one day inform forecasts of these intense bursts of solar radiation.

As it progresses through its natural 11-year cycle, the Sun transitions from periods of high to low activity, and back to high again. The scientists focused on X-class flares, the most powerful kind of these solar fireworks. Compared to smaller flares, big flares like these are relatively infrequent; in the last solar cycle, there were around 50. But they can have big impacts, from disrupting radio communications and power grid operations, to — at their most severe — endangering astronauts in the path of harsh solar radiation. Scientists who work on modeling flares hope that one day their efforts can help mitigate these effects.

Led by Kanya Kusano, the director of the Institute for Space-Earth Environmental Research at Japan’s Nagoya University, a team of scientists built their model on a kind of magnetic map: SDO’s observations of magnetic fields on the Sun’s surface. Their results were published in Science on July 30, 2020.

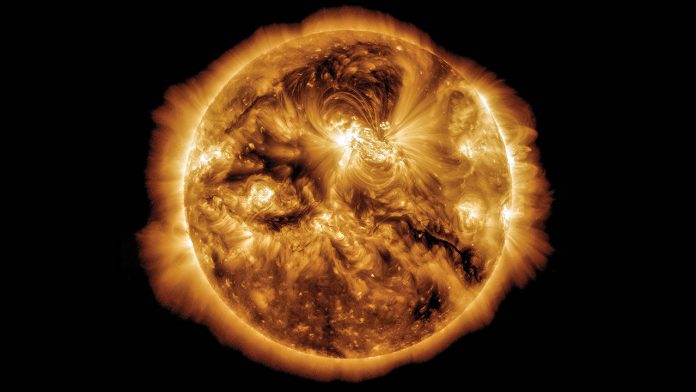

It’s well-understood that flares erupt from hot spots of magnetic activity on the solar surface, called active regions. (In visible light, they appear as sunspots, dark blotches that freckle the Sun.) The new model works by identifying key characteristics in an active region, characteristics the scientists theorized are necessary to setting off a massive flare.

The first is the initial trigger. Solar flares, especially X-class ones, unleash huge amounts of energy. Before an eruption, that energy is contained in twisting magnetic field lines that form unstable arches over the active region. According to the scientists, highly twisted rope-like lines are a precursor for the Sun’s biggest flares. With enough twisting, two neighboring arches can combine into one big, double-humped arch. This is an example of what’s known as magnetic reconnection, and the result is an unstable magnetic structure — a bit like a rounded “M” — that can trigger the release of a flood of energy, in the form of a flare.

Where the magnetic reconnection happens is important too, and one of the details the scientists built their model to calculate. Within an active region, there are boundaries where the magnetic field is positive on one side and negative on the other, just like a regular refrigerator magnet.

“It’s similar to an avalanche,” Kusano said. “Avalanches start with a small crack. If the crack is up high on a steep slope, a bigger crash is possible.” In this case, the crack that starts the cascade is magnetic reconnection. When reconnection happens near the boundary, there’s potential for a big flare. Far from the boundary, there’s less available energy, and a budding flare can fizzle out — although, Kusano pointed out, the Sun could still unleash a swift cloud of solar material, called a coronal mass ejection.

Kusano and his team looked at the seven active regions from the last solar cycle that produced the strongest flares on the Earth-facing side of the Sun (they also focused on flares from part of the Sun that is closest to Earth, where magnetic field observations are best). SDO’s observations of the active regions helped them locate the right magnetic boundaries, and calculate instabilities in the hot spots. In the end, their model predicted seven out of nine total flares, with three false positives. The two that the model didn’t account for, Kusano explained, were exceptions to the rest: Unlike the others, the active region they exploded from were much larger, and didn’t produce a coronal mass ejection along with the flare.

“Predictions are a main goal of NASA’s Living with a Star program and missions,” said Dean Pesnell, the SDO principal investigator at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, who did not participate in the study. SDO was the first Living with a Star program mission. “Accurate precursors such as this that can anticipate significant solar flares show the progress we have made towards predicting these solar storms that can affect everyone.”

While it takes a lot more work and validation to get models to the point where they can make forecasts that spacecraft or power grid operators can act upon, the scientists have identified conditions they think are necessary for a major flare. Kusano said he is excited to have a promising first result.

“I am glad our new model can contribute to the effort,” he said.