[ad_1]

During germination, the embryo within the seed must develop into a young seedling capable of photosynthesis in less than 48 hours. During this time, it relies solely on its internal reserves, which are quickly consumed. It must therefore rapidly create functional chloroplasts, cellular organelles that will enable it to produce sugars to ensure its survival. Researchers from the University of Geneva (UNIGE) and the University of Neuchâtel (UniNE), Switzerland, have revealed in the journal Current Biology the key elements that control the formation of chloroplasts from proplastids, hitherto poorly studied organelles. Such a mechanism ensures a rapid transition to autonomous growth, as soon as the seed decides to germinate.

The surprising propagation and diversification of flowering plants in terrestrial environments are mainly due to the appearance of seeds during evolution. The embryo, which is dormant, is encapsulated and protected in a very resistant structure, which facilitates its dispersion. At this stage, it cannot perform photosynthesis and, during germination, it will thus consume the nutritive reserves stored in the seed. This process induces the transformation of a strong embryo into a fragile seedling. “This is a critical stage in the life of a plant, which is closely regulated, notably by the growth hormone gibberellic acid (GA). The production of this hormone is repressed when external conditions are unfavorable,” explains Luis Lopez-Molina, Professor at the Department of Botany and Plant Biology of the UNIGE Faculty of Science.

Import proteins submitted to the cell shredder

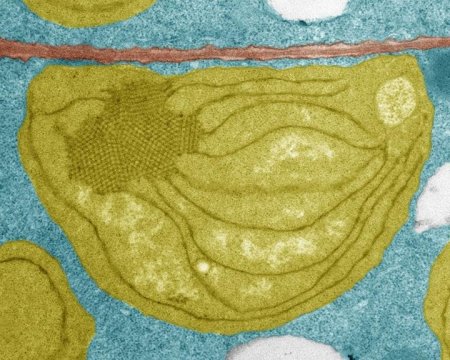

The awakening of the embryo causes the differentiation of its proplastids into chloroplasts, biological factories capable of producing sugar thanks to photosynthesis. “Thousands of different proteins must be imported into the developing chloroplasts, and this process can only take place in the presence of a protein called TOC159. If it is lacking, the plant will be depleted in chloroplasts and will remain albino,” explains Felix Kessler, Director of the Plant Physiology Lab and Vice-Rector of the UniNE.

How does the seed decide whether to keep the embryo in a protected state or, on the contrary, to take a chance and let it germinate? “We have discovered that, as long as GA is suppressed, a mechanism is set up, which ensures that TOC159 proteins are transported to the cellular waste bin in order to be degraded,” explains Venkatasalam Shanmugabalaji, researcher within the Neuchâtel group and first author of the study. In addition, other proteins needed for photosynthesis, of which TOC159 facilitates importation, suffer the same fate.

A high-performance biomechanism

When external conditions become favorable for germination, the GA concentration increases in the seed. The biologists discovered that high concentrations of this hormone indirectly block the degradation of TOC159 proteins. The latter can therefore be inserted into the membrane of the proplastids and enable the import of photosynthetic proteins cargoes, which also escape the cellular waste bin.

The genesis of the first functional chloroplasts, implemented in less than 48 hours, therefore ensures a rapid transition from a growth depending on the embryo’s reserves to an autonomous development. This high-performance mechanism contributes to the survival of the seedling in an inhospitable environment, in which it will have to face many challenges.

Story Source:

Materials provided by Université de Genève. Note: Content may be edited for style and length.

[ad_2]