[ad_1]

The growth of forest trees all over the world is becoming more water-limited as the climate warms, according to new research from an international team that includes University of Arizona scientists.

The effect is most evident in northern climates and at high altitudes where the primary limitation on tree growth had been cold temperatures, reports the team this week in the online journal Science Advances.

“Our study shows that across the vast majority of the land surface, trees are becoming more limited by water,” said first author Flurin Babst, who conducted the research at the UA Laboratory of Tree-Ring Research and the Swiss Federal Research Institute WSL in Zurich.

“This is the first time that anybody has projected the tree growth responses to climate at a near-global scale,” Babst said.

The researchers compared the annual growth rings of trees during two time periods, 1930-1960 and 1960-1990. The growth rings are wider when conditions are better, narrower when conditions are worse. The ring-width measurements were taken from trees at about 2,700 sites spanning every continent except Antarctica.

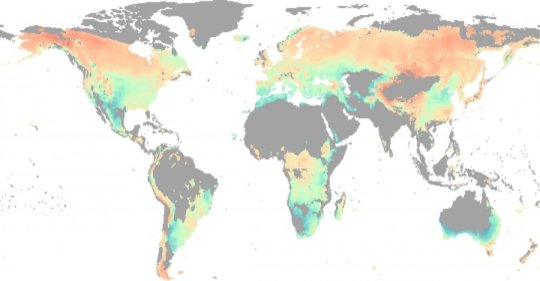

For those two time periods, the team also mapped average temperature, precipitation and measures of drought stress on plants onto a grid covering the world’s temperate and boreal regions.

Adding tree-ring data to the map allowed scientists to see whether the changes in climate during the 20th century corresponded to the changes in growth of the world’s trees.

UA co-author David Frank said, “We saw areas where, in the earlier part of the 20th century, temperature limited growth. But now we are seeing shifts towards moisture-drought limitation.”

Comparing 1930-1960 with 1960-1990, the average temperature increased 0.9 degrees F (0.5 degrees C) and the land area where tree growth was primarily limited by temperature shrank by 3.3 million square miles (8.7 million square kilometers), an area about the size of Brazil.

Babst was surprised that such a small change in temperature would shift such a large area of trees from being temperature-limited to being water-limited.

“That’s much more than I expected,” said Babst, who is now a research scientist at the Swiss Federal Research Institute WSL.

The finding has implications for future forest and tree growth and for forest management, said Frank, director of the Laboratory of Tree-Ring Research and professor of dendrochronology at the UA.

“Reduced growth is indicative of increased stress on plants — which can be linked to mortality,” he said.

The team’s paper “Twentieth century redistribution in climatic drivers of global tree growth” is scheduled for online publication in Science Advances on January 16. More information on co-authors and funding agencies is at the bottom of this news release.

Since the advent of systematic satellite observations in the late 1970s, scientists can now study changes in vegetation growth over large areas by comparing satellite images of the same place over time and measuring “greenness” in the images. Greenness is a measure of how leafy the plants are and how fast they are growing.

However, satellite observations weren’t available for most of the 20th century. Moreover, measuring “greenness” in a satellite image can’t tell how much individual plants grew from year to year.

“Satellites only see the leaves — they don’t see the wood where the carbon is stored,” Babst said. “We wanted to provide a wood perspective.”

He and his colleagues wanted on-the-ground measurements of tree growth to compare to the data from satellites. By using several databases of tree-ring measures from all over the world for the time periods 1930-1960 and 1960-1990, the researchers could see whether the average growth of trees had changed.

In addition, because the team’s research combines the substantial database of growth data from tree rings all over the world with global climate data for the same time period, the new results will help test and improve computer models of how climate affects vegetation, Frank said.

Babst and Frank’s co-authors are Valerie Trouet of the UA; Olivier Bouriaud of Strada Universit?t in Suceava, Romania; Benjamin Poulter of the NASA Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland; and Martin P. Girardin of Natural Resources Canada in Quebec and the Université du Québec à Montréal, Canada.

The European Union-Horizon 2020 program and the Swiss National Science Foundation funded the research.

[ad_2]