[ad_1]

Scientists at the U.S. Department of Energy’s National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) have developed a recycling process that transforms single-use beverage bottles, clothing, and carpet made from the common polyester material polyethylene terephthalate (PET) into more valuable products with a longer lifespan. Their research, published February 27 in the journal Joule, could help protect oceans from plastic waste by jumpstarting the recycled plastics market.

PET is strong but lightweight, resistant to water, and shatterproof — properties that make it extremely popular among manufacturers. Although PET is recyclable, most of the 26 million tons produced every year ends up in landfills or elsewhere in the environment, where it takes hundreds of years to biodegrade. But even when it is recycled, the process is far from perfect. Reclaimed PET has a lower value than the original and can only be repurposed once or twice.

“Standard PET recycling today is essentially ‘downcycling,'” says senior author Gregg Beckham, a Senior Research Fellow at NREL. “The process we came up with is a way to ‘upcycle’ PET into long-lifetime, high-value composite materials like those that would be used in car parts, wind turbine blades, surfboards, or snowboards.”

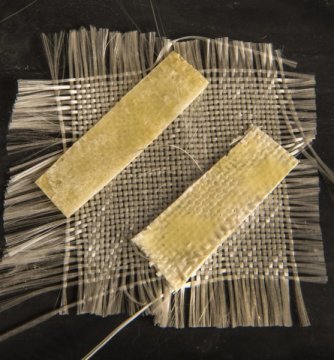

The team combined reclaimed PET with building blocks derived from renewable sources such as waste plant biomass. This resulted in a new material that combines reclaimed PET and sustainably sourced, bio-based molecules to produce two types of fiber-reinforced plastics (FRPs), which are 2-3 times more valuable than the original PET, meaning that future plastic bottles could live lucrative second lives. Through their collaboration with analysts at NREL, the team also predicts that the composite product would require 57% less energy to produce than reclaimed PET using the current recycling process and would emit 40% fewer greenhouse gases than standard petroleum-based FRPs — a significant improvement over business as usual.

“The idea is to develop technologies that would incentivize the economics of PET reclamation,” says Beckham. “That’s the real hope — to develop ‘second-life’ upcycling technologies that make single-use waste plastic valuable to reclaim. This, in turn, could help keep waste plastic out of the world’s oceans and out of landfills.”

But there is still work to be done before this recycling process can be implemented beyond the laboratory bench. The team plans to further analyze the properties of the composite materials that result when PET is combined with the plant-based monomers and to test the process for scalability to determine how well it might fare in a manufacturing setting. They also hope to develop composites that can themselves be recycled; the current composites can last years and even decades but are not necessarily recyclable in the end. In addition, the NREL team plans to develop similar technologies for recycling other types of materials.

“The scale of PET production dwarfs that of composites manufacturing, so we need many more upcycling solutions to truly make a global impact on plastics reclamation through technologies like the one proposed in the current study,” says first author Nicholas Rorrer, an engineer at NREL who also participated in the study.

Story Source:

Materials provided by Cell Press. Note: Content may be edited for style and length.

[ad_2]