[ad_1]

A new study led by researchers at the American Museum of Natural History looks at the genes behind an incredible, luminous seasonal mating display produced by swarms of bioluminescent marine Bermuda fireworms. The new research, published today in the journal PLOS ONE, confirms that the enzymes responsible for the fireworms’ glow are unique among bioluminescent animals and entirely unlike those seen in fireflies. The study also examines genes associated with some of the dramatic — and reversible — changes that happen to the fireworms during reproduction.

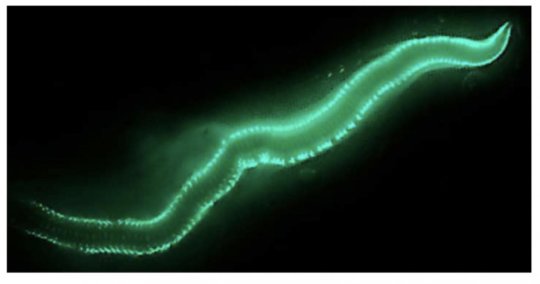

The beautiful bioluminescence of the Bermuda fireworm (Odontosyllis enopla), which lives throughout the Caribbean, was first documented in 1492 by Christopher Columbus and his crew just before landing in the Americas. The observations described the lights as “looking like the flame of a small candle alternately raised and lowered.”

The phenomenon went unexplained until the 1930s, when scientists matched the historic description with the unusual and precisely timed mating behavior of fireworms. During summer and autumn, beginning at 22 minutes after sunset on the third night after the full Moon, spawning female fireworms secrete a bright bluish-green luminescence that attracts males. “It’s like they have pocket watches,” said lead author Mercer R. Brugler, a Museum research associate and assistant professor at New York City College of Technology (City Tech).

“The female worms come up from the bottom and swim quickly in tight little circles as they glow, which looks like a field of little cerulean stars across the surface of jet black water,” said Mark Siddall, a curator in the American Museum of Natural History’s Division of Invertebrate Zoology and corresponding author of the study. “Then the males, homing in on the light of the females, come streaking up from the bottom like comets — they luminesce, too. There’s a little explosion of light as both dump their gametes in the water. It is by far the most beautiful biological display I have ever witnessed.”

To further investigate this phenomenon, Siddall, together with Brugler; Michael Tessler, a postdoctoral fellow in the Museum’s Sackler Institute for Comparative Genomics, and M. Teresa Aguado, former postdoctoral fellow in the Museum’s Sackler Institute for Comparative Genomics who is now at the Autonomous University of Madrid, analyzed the transcriptome — the full set of RNA molecules — of a dozen female fireworms from Ferry Reach in Bermuda.

Their findings support previous work showing that fireworms “glow” because of a special luciferase enzyme they produce. These enzymes are the principal drivers of bioluminescence across the tree of life, in organisms as diverse as copepods, fungi, and jellyfish. However, the luciferases found in Bermuda fireworms and their relatives are distinct from those found in any other organism to date.

“It’s particularly exciting to find a new luciferase because if you can get things to light up under particular circumstances, that can be really useful for tagging molecules for biomedical research,” said Tessler.

The work also took a close look at genes related to the precise reproductive timing of the fireworms, as well as the changes that take place in the animals’ bodies just prior to swarming events. These changes include the enlargement and pigmentation of the worms’ four eyes and the modification of the nephridia — an organ similar to the kidney in vertebrates — to store and release gametes.

Story Source:

Materials provided by American Museum of Natural History. Note: Content may be edited for style and length.

[ad_2]