[ad_1]

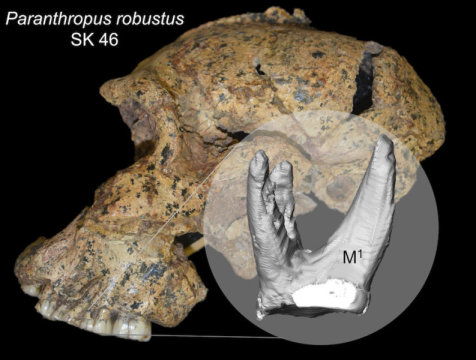

Since the discovery of the fossil remains of Australopithecus africanus from Taung nearly a century ago, and subsequent discoveries of Paranthropus robustus, there have been disagreements about the diets of these two South African hominin species. By analyzing the splay and orientation of fossil hominin tooth roots, researchers of the MPI for Evolutionary Anthropology, the University of Chile and the University of Oxford now suggest that Paranthropus robustus had a unique way of chewing food not seen in other hominins.

Food needs to be broken down in the mouth before it can be swallowed and digested further. How this is being done depends on many factors, such as the mechanical properties of the foods and the morphology of the masticatory apparatus. Palaeoanthropologists spend a great deal of their time reconstructing the diets of our ancestors, as diet holds the key to understanding our evolutionary history. For example, a high-quality diet (and meat-eating) likely facilitated the evolution of our large brains, whilst the lack of a nutrient-rich diet probably underlies the extinction of some other species (e.g., P. boisei). The diet of South African hominins has remained particularly controversial however.

Using non-invasive high-resolution computed tomography technology and shape analysis the authors deduced the main direction of loading during mastication (chewing) from the way the tooth roots are oriented within the jaw. By comparing the virtual reconstructions of almost 30 hominin first molars from South and East Africa they found that Australopithecus africanus had much wider splayed roots than both Paranthropus robustus and the East African Paranthropus boisei. “This is indicative of increased laterally-directed chewing loads in Australopithecus africanus, while the two Paranthropus species experienced rather vertical loads,” says Kornelius Kupczik of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology.

Paranthropus robustus, unlike any of the other species analysed in this study, exhibits an unusual orientation, i.e. “twist,” of the tooth roots, which suggests a slight rotational and back-and-forth movement of the mandible during chewing. Other morphological traits of the P. robustus skull support this interpretation. For example, the structure of the enamel also points towards a complex, multidirectional loading, whilst their unusual microwear pattern can conceivably also be reconciled with a different jaw movement rather than by mastication of novel food sources. Evidently, it is not only what hominins ate and how hard they bit that determines its skull morphology, but also the way in which the jaws are being brought together during chewing.

The new study demonstrates that the orientation of tooth roots within the jaw has much to offer for an understanding of the dietary ecology of our ancestors and extinct cousins. “Perhaps palaeoanthropologists have not always been asking the right questions of the fossil record: rather than focusing on what our extinct cousins ate, we should equally pay attention to how they masticated their foods,” concludes Gabriele Macho of the University of Oxford.

Molar root variation in hominins is therefore telling us more than previously thought. “For me as an anatomist and a dentist, understanding how the jaws of our fossil ancestors worked is very revealing as we can eventually apply such findings to the modern human dentition to better understand pathologies such as malocclusions,” adds Viviana Toro-Ibacache from the University of Chile and one of the co-authors of the study.

Story Source:

Materials provided by Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology. Note: Content may be edited for style and length.

[ad_2]