[ad_1]

Ohio University researchers announced a new species of mammal from the Age of Dinosaurs, representing the most complete mammal from the Cretaceous Period of continental Africa, and providing tantalizing insights into the past diversity of mammals on the planet.

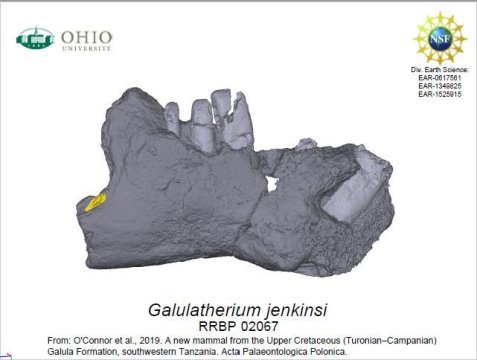

The National Science Foundation-funded OHIO team, in collaboration with international colleagues, identified and named the new mammal in an article published today in Acta Paleontologica Polonica. This nearly complete lower jaw represents the first named mammal species from the Late Cretaceous Period (100-66 million years ago) of the entire African continent. The squirrel-sized animal was probably related to a group of southern hemisphere mammals known as gondwanatherians, yet a bizarre combination of features (including evergrowing and enamel-less peg-like teeth) make it challenging to easily place within any group of mammals yet known, living or extinct.

The new mammal is named Galulatherium jenkinsi, a name based on the Galula rock unit (itself derived from one of the local villages in the field area) and therium, Latin for beast, with the species name “jenkinsi” honoring the late Farish Jenkins, distinguished professor of anatomy and organismic biology at Harvard University and a strong supporter of the Rukwa Rift Basin Project early in its development.

The type and only specimen of Galulatherium was discovered in 2002, when Rukwa Rift Basin Project researchers found a bone fragment eroding from Cretaceous-age red sandstones in the Rukwa Rift Basin in southwestern Tanzania. After painstakingly removing the rock from the delicate specimen, the team announced the discovery of a new mammal in 2003, yet they conservatively refrained from establishing a name for the enigmatic new species until additional details of its anatomy could be revealed. In the intervening years, improvements in high-resolution x-ray computed tomography enabled the team to document detailed anatomy of the specimen and to establish Galulatherium as a species new to science.

“The analysis of Galulatherium has been a collaborative process, engaging with a group of experts to tackle the unique morphology of this specimen,” noted Dr. Patrick O’Connor, professor of anatomy at Ohio University and lead author of the paper. “Additional information gleaned from density-based microCT analyses, particularly the presence of ever-growing, enamel-less teeth, has allowed us to compare Galulatherium with other Mesozoic and early Cenozoic mammals, as well as with modern groups like sloths, in order to establish the best anatomical and functional analogs for this unique type of dentition.”

Gonwanatherian mammals are best known from Cretaceous and early Cenozoic rock units in Madagascar and Argentina, with other specimens known from India and Antarctica. Members of the research team have worked across the globe in search of early mammals.

“The fact that this is the first discovery of an identifiable mammal fossil in the Late Cretaceous of all of mainland Africa is incredibly exhilarating on so many levels,” added co-author David Krause, curator of paleontology at the Denver Museum of Nature and Science. “The needle is very small and the haystack is very big. And we know that there are so many more needles to find there.”

The perplexing story of Galulatherium and identifying its closest relatives is just the starting point. Getting ANY insight into what mammals lived on the continent during this time is groundbreaking, but it seems that Galulatherium is not a predecessor of any of the mammals that live on Africa today. So what happened to it and its kin? Were they wiped out at the end of the Cretaceous? When did the ancestors of Africa’s extant mammalian lineages arrive on the continent? Or were they living alongside Galulatherium and just have not yet been found?

“All great questions that will only be answered with the discovery of additional fossils, underscoring the need for exploratory research in places like the Rukwa Rift Basin and elsewhere on the continent,” added O’Connor.

The study included experts from several institutions to pore over the tiny jaw. Yet the specimen preserved a truly unique combination of anatomical features, making it difficult to place in the existing framework of mammalian evolution, and ultimately raising more questions than it answers.

“What began with the description of a compact specimen became a broader quest to understand how this jaw fits into the complex puzzle of mammalian evolution,” said Dr. Nancy Stevens, Ohio University professor and co-author on the paper.

Galulatherium is not the only animal discovered by the research team in the Rukwa Rift Basin. Other Cretaceous-age finds include bizarre relatives of early crocodiles and three distinct species of long-necked herbivorous sauropod dinosaurs. Finds from younger rocks in the region contain the oldest evidence of the split between monkeys and apes. Taken together, these findings from the East African Rift reveal a crucial glimpse into ancient ecosystems of Africa and encourage additional field exploration on the continent.

Other Cretaceous findings by the Rukwa Rift Basin Project research team in the Rukwa Rift Basin include:

- Mnyamawantuka moyowamkia — titanosaurian sauropod dinosaur, Rukwa Rift Basin

- Shingopana songwensis — titanosaurian sauropod dinosaur, Rukwa Rift Basin

- Rukwatitan bisepultus — titanosaurian sauropod dinosaur, Rukwa Rift Basin

- Pakasuchus kapilimai — mammal-like crocodile, Rukwa Rift Basin

The team has also made discoveries in the younger Paleogene deposits of the Rukwa Rift Basin:

- Early evidence for monkey-ape split, Rukwa Rift Basin

- Oldest fossil evidence of venomous snakes, Rukwa Rift Basin

- Early evidence of insect farming — Fossil Termite Nests, Rukwa Rift Basin

- Bobcat-sized carnivore, Rukwa Rift Basin

The study was funded by the US National Science Foundation Division of Earth Sciences, the National Geographic Society, the Ohio University Heritage College of Osteopathic Medicine, and the OHIO Office of the Vice President for Research and Creative Activity.

Story Source:

Materials provided by Ohio University. Note: Content may be edited for style and length.

[ad_2]