[ad_1]

The earthquakes are so small and deep that someone standing in Seattle would never feel them. In fact, until the early 2000s, nobody knew they happened at all. Now, scientists at Rice University have unearthed details about the structure of Earth where these tiny tremors occur.

Rice postdoctoral researcher and seismologist Jonathan Delph and Earth scientists Fenglin Niu and Alan Levander make a case for the incursion of fluid related to slippage deep inside the Cascadia margin off the Pacific Northwest’s coast.

Their paper, which appears in the American Geophysical Union journal Geophysical Research Letters, links fluids escaping from deep subduction to the frequent shakes that Delph said happen in relative slow motion when compared to the sudden, violent jolts occasionally felt by Southern Californians at the southern end of the west coast.

“These aren’t large, instantaneous events like a typical earthquake,” Delph said. “They’re seismically small, but there’s a lot of them and they are part of the slow-slip type of earthquake that can last for weeks instead of seconds.”

Delph’s paper is the first to show variations in the scale and extent of fluids that come from dehydrating minerals and how they relate to these low-velocity quakes. “We are finally at the point where we can address the incredible amount of research that’s been done in the Pacific Northwest and try to bring it all together,” he said. “The result is a better understanding of how the seismic velocity structure of the margin relates to other geologic and tectonic observations.”

The North American plate and Juan de Fuca plate, a small remnant of a much larger tectonic plate that used to subduct beneath North America, meet at the Cascadia subduction zone, which extends from the coast of northern California well into Canada. As the Juan de Fuca plate moves to the northeast, it sinks below the North American plate.

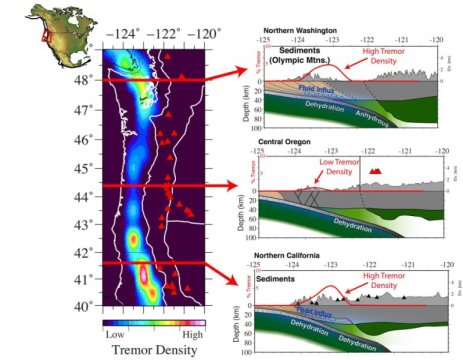

Delph said fluids released from minerals as they heat up at depths of 30 to 80 kilometers propagate upward along the boundary of the plates in the northern and southern portions of the margin, and get trapped in sediments that are subducting beneath the Cascadia margin.

“This underthrust sedimentary material is being stuck onto the bottom of the North American plate,” he said. “This can allow fluids to infiltrate. We don’t know why, exactly, but it correlates well with the spatial variations in tremor density we observe. We’re starting to understand the structure of the margin where these tremors are more prevalent.”

Delph’s research is based on extensive seismic records gathered over decades and housed at the National Science Foundation-backed IRIS seismic data repository, an institutional collaboration to make seismic data available to the public.

“We didn’t know these tremors existed until the early 2000s, when they were correlated with small changes in the direction of GPS stations at the surface,” he said. “They’re extremely difficult to spot. Basically, they don’t look like earthquakes. They look like periods of higher noise on seismometers.

“We needed high-accuracy GPS and seismometer measurements to see that these tremors accompany changes in GPS motion,” Delph said. “We know from GPS records that some parts of the Pacific Northwest coast change direction over a period of weeks. That correlates with high-noise ‘tremor’ signals we see in the seismometers. We call these slow-slip events because they slip for much longer than traditional earthquakes, at much slower speeds.”

He said the phenomenon isn’t present in all subduction zones. “This process is pretty constrained to what we call ‘hot subduction zones,’ where the subducting plate is relatively young and therefore warm,” Delph said. “This allows for minerals that carry water to dehydrate at shallower depths.

“In ‘colder’ subduction zones, like central Chile or the Tohoku region of Japan, we don’t see these tremors as much, and we think this is because minerals don’t release their water until they’re at greater depths,” he said. “The Cascadia subduction zone seems to behave quite differently than these colder subduction zones, which generate large earthquakes more frequently than Cascadia. This could be related in some way to these slow-slip earthquakes, which can release as much energy as a magnitude 7 earthquake over their duration. This is an ongoing area of research.”

Story Source:

Materials provided by Rice University. Original written by Mike Williams. Note: Content may be edited for style and length.

[ad_2]