[ad_1]

Scientists at the Salk Institute found that mice lacking the biological clocks thought to be necessary for a healthy metabolism could still be protected against obesity and metabolic diseases by having their daily access to food restricted to a 10-hour window.

The work, which appeared in the journal Cell Metabolism on August 30, 2018, suggests that the health problems associated with disruptions to animals’ 24-hour rhythms of activity and rest — which in humans is linked to eating for most of the day or doing shift work — can be corrected by eating all calories within a 10-hour window.

“For many of us, the day begins with a cup of coffee first thing in the morning and ends with a bedtime snack 14 or 15 hours later,” says Satchidananda Panda, a professor in Salk’s Regulatory Biology Laboratory and the senior author of the new paper. “But restricting food intake to 10 hours a day, and fasting the rest, can lead to better health, regardless of our biological clock.”

Every cell in mammals’ bodies operates on a 24-hour cycle known as the circadian rhythm — cellular cycles that govern when various genes are active. For example, in humans, genes for digestion are more active earlier in the day while genes for cellular repair are more active at night. Previously, the Panda lab discovered that mice allowed 24-hour access to a high-fat diet became obese and developed a slew of metabolic diseases including high cholesterol, fatty liver and diabetes. But these same mice, when restricted to the high-fat diet for a daily 8- to 10-hour window became lean, fit and healthy. The lab attributed the health benefits to keeping the mice in better sync with their cellular clocks — for example, by eating most of the calories when genes for digestion were more active.

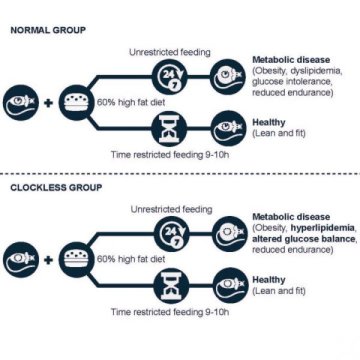

In the current study, the team aimed to better understand the role of circadian rhythms in metabolic diseases by disabling genes responsible for maintaining the biological clock in mice, including in the liver, which regulates many metabolic functions. The genetic defects in these clock-less mice make them prone to obesity, diabetes, fatty liver disease and elevated blood cholesterol. These diseases further escalate when the animals are allowed to eat fatty and sugary food.

To test whether time-restricted eating could benefit these “clock-less” mice, Panda’s team put them on one of two high-fat diet regimes: one group had access to food around the clock, the other had access to the same number of calories only during a 10-hour window. As the team expected, the group that could eat at any time became obese and developed metabolic diseases. But the group that ate the same number of calories within a 10-hour window remained lean and healthy — despite not having an internal “biological clock” and thereby genetically programmed to be morbidly sick. This told the researchers that the health benefits from a 10-hour window were not just due to restricting eating to times when genes for digestion were more active.

“From the previous study, we had been under the impression that the biological clock was internally timing the process of turning genes for metabolism on and off at predetermined times,” says Amandine Chaix, a staff scientist at Salk and the paper’s first author. “And while that may still be true, this work suggests that by controlling the animals’ feeding and fasting cycles, we can basically override the lack of an internal timing system with an external timing system.”

According to the researchers, the new work suggests that the primary role of circadian clocks may be to tell the animal when to eat and when to stay away from food. This internal timing strikes a balance between sufficient nutrition during the fed state and necessary repair or rejuvenation during fasting. When this circadian clock is disrupted, as when humans do shift work, or when it is compromised due to genetic defects, the balance between nutrition and rejuvenation breaks down and diseases set in.

As we age, our circadian clocks weaken. This age-dependent deterioration of circadian clock parallels our increased risk for metabolic diseases, heart diseases, cancer and dementia.

But the good news, say the researchers, is that a simple lifestyle such as eating all food within 10 hours can restore balance, stave off metabolic diseases and maintain health. “Many of us may have one or more disease-causing defective genes that make us feel helpless and destined to be sick. The finding that a good lifestyle can beat the bad effects of defective genes opens new hope to stay healthy,” says Panda.

The lab next plans to study whether eating within 8-10 hours can prevent or reverse many diseases of aging, as well as looking at how the current study could apply to humans. Their website, mycircadianclock.org, allows people anywhere in the world to sign up for studies, download an app and get guidance on how to adopt an optimum daily eating-fasting cycle. By collecting daily eating and health status data from thousands of people, the lab hopes to gain a better understanding of how a daily eating-fasting cycle sustains health.

[ad_2]