The Red Planet’s low gravity and lack of magnetic field makes its outermost atmosphere an easy target to be swept away by the solar wind, but new evidence from ESA’s Mars Express spacecraft shows that the Sun’s radiation may play a surprising role in its escape.

Why the atmospheres of the rocky planets in the inner Solar System evolved so differently over 4.6 billion years is key to understanding what makes a planet habitable. While Earth is a life-rich water-world, our smaller neighbour Mars lost much of its atmosphere early in its history, transforming from a warm and wet environment to the cold and arid plains that we observe today. By contrast, Earth’s other neighbour Venus, which although inhospitable today is comparable in size to our own planet, and has a dense atmosphere.

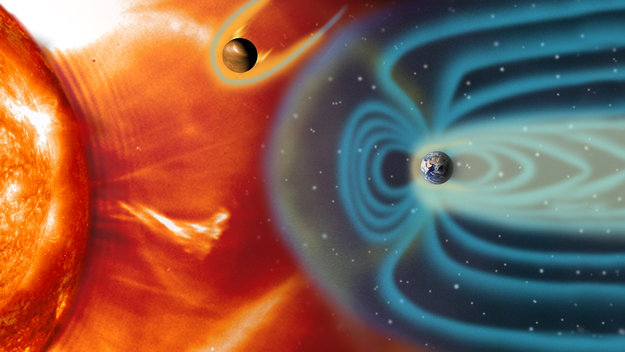

One way that is often thought to help protect a planet’s atmosphere is through an internally generated magnetic field, such as at Earth. The magnetic field deflects charged particles of the solar wind as they stream away from the Sun, carving out a protective ‘bubble’ – the magnetosphere – around the planet.

At Mars and Venus, which don’t generate an internal magnetic field, the main obstacle to the solar wind is the upper atmosphere, or ionosphere. Just as on Earth, solar ultraviolet radiation separates electrons from the atoms and molecules in this region, creating a region of electrically charged – ionised – gas: the ionosphere. At Mars and Venus this ionised layer interacts directly with the solar wind and its magnetic field to create an induced magnetosphere, which acts to slow and divert the solar wind around the planet.

For 14 years, ESA’s Mars Express has been looking at charged ions, such as oxygen and carbon dioxide, flowing out to space in order to better understand the rate at which the atmosphere is escaping the planet.

The study has uncovered a surprising effect, with the Sun’s ultraviolet radiation playing a more important role than previously thought.

“We used to think that the ion escape occurs due to an effective transfer of the solar wind energy through the martian induced magnetic barrier to the ionosphere,” says Robin Ramstad of the Swedish Institute of Space Physics, and lead author of the Mars Express study.

“Perhaps counter-intuitively, what we actually see is that the increased ion production triggered by ultraviolet solar radiation shields the planet’s atmosphere from the energy carried by the solar wind, but very little energy is actually required for the ions to escape by themselves, due to the low gravity binding the atmosphere to Mars.”