[ad_1]

University of Oregon anthropologist Klaree Boose followed her intuition about her observations of bonobos at a U.S. zoo. She now theorizes that young females of the endangered ape species prepare for motherhood and form social bonds by helping mothers take care of infants.

“After studying bonobos for several years, I noticed that immature individuals of juveniles and adolescents were obsessed with the babies,” said Boose, an instructor in the UO Department of Anthropology. “They played with the babies and carried them around. It appeared to be more than just play behavior.”

While multiple theories exist about such behaviors in primates, Boose realized, they had not been examined in bonobos. So, she led a project at the Columbus Zoo and Aquarium in Ohio, to focus on spontaneous activity of the bonobos and collect urine samples from juveniles and adolescents.

Eventually, two clear findings emerged. Young females that handle the infants of mothers are building maternal skills they will eventually need and forging alliances with the mothers that pay off in times of hostility.

The research, which drew upon 1,819 hours of observations of 11 females and eight males during summer months of 2011-2015, was published online in May ahead of print as part of a special issue for the journal Physiology & Behavior.

Bonobos (Pan paniscus) in the wild live only in a small area of the Congo Basin in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. They are often thought to be chimpanzees, but, they are a separate species than common chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes). Bonobo females hold the highest rank positions and often form female-female coalitions that team up against males.

The findings were a bit surprising, Boose said. “Like all ape species, bonobo females don’t need somebody to help them take care of their infants,” she said. “They are perfectly capable of doing it themselves.”

Initially, Boose observed that female and male bonobos as juveniles — those 3 to 7 years old — were obsessed with handling the infants, all under age 3, regardless of their relationships with the mothers. As young bonobos entered adolescence at age 8, however, females continued to approach the mothers and help care for the infants, while males turned away in favor of other behaviors.

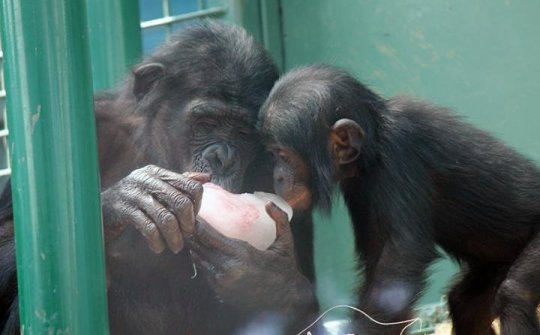

“Handling behavior picked up among the female adolescents, and it was really intense,” Boose said. “They would approach the mothers, groom them briefly and then carry the babies away. They’d move across the enclosure where they would engage in nurturing and other maternal behaviors with the infants, such as grooming and cradling them, putting them on their belly and carrying them on their back. These were very deliberate caretaking behaviors.”

The connection between infant handling to prepare for motherhood and forging bonds with the mothers was seen in hormone production. Elevated levels of oxytocin — associated with complex social behaviors and social cognition, including maternal and caregiving activities — were found among many of the 401 urine samples collected after bonobos engaged in infant-handling activities.

As young females interact with the infants, Boose said, the increased oxytocin production may reflect how the body is biologically reinforcing in a positive way either the caregiving activity or social bonding with mothers or infants.

The social bonding also reaped dividends for the young female bonobos. Mothers were seen coming to the aid of younger females that had handled their infants when conflicts arose over access to food and other fighting situations.

“When a fight involved a handler, particularly the adolescent females, the mother would help the individual that had handled her infant attack the aggressor, usually an adolescent or adult male but sometimes another female,” Boose said. “They would intervene and support them.”

The researchers cautioned that the study was exploratory. The work, however, provides preliminary evidence for where bonobos may or may not fit among the various theories about infant handling among primates.

“This work was done in a captive population, and we had a finite amount of time,” Boose said. “Ideally, we’d do this in a wild population and we’d be able to track these animals over multiple generations.”

Co-author Frances White, who heads the UO Department of Anthropology and has extensively studied bonobos in Africa, said the study provides helpful information.

“It is common in the wild to see infant bonobos be a focus of enormous interest to others, especially to adolescent bonobos,” White said. “It is often noticeable how bonobo mothers are willing to let others get close and interact with their infants, as compared to chimpanzees who are more restrictive.”

This study, White said, allowed the team to take that knowledge and explore individual relationships in a way that has not been done in the wild.

“The Columbus Zoo has done a wonderful job of copying wild behavior in letting the bonobos divide on a day-by-day basis into different groupings, much as they do in the wild,” she said. “This zoo setting made this kind of study, which looks at normal wild behaviors, possible.

[ad_2]