[ad_1]

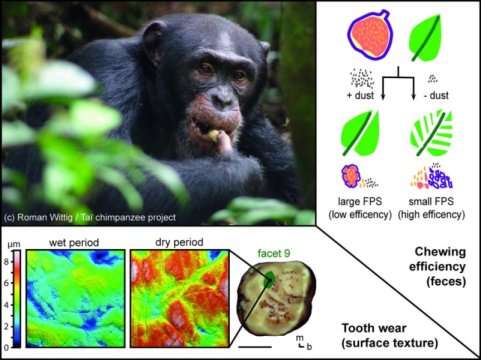

In their study, the researchers collected feces from chimpanzees living at Taï National Park, Ivory Coast, and analyzed chewing efficiency during dry and rainy periods. They found that increased dust loads during dry periods result in decreased chewing efficiency. Moreover, it was tested how dust affects tooth wear (surface texture) of the chimpanzees. The researchers found that consumption of dust covered foods created micrometer-scale surface texture features (e.g. fine furrows and dales) on cheek teeth while at the same time chewing was less intensive resulting in a lower amount of chews per food ingested and subsequently in larger mean fecal particle sizes.

What is more, the Leipzig researchers found evidence that abrasive loads from regionally (the West African subcontinent) acting periodical dust winds represent an ecological constraint on a local environment. The chimpanzees from the Taï forest are therefore one of the rarely described examples in African terrestrial environments where dust loads can be quantified and directly related to tooth wear.

In addition, the researchers explored the relationship between tooth wear and dietary composition using the long-term observation database on chimpanzee behavior of the Taï chimpanzee project and compiled observational data for feeding durations for the years 1993-2009. It was found that adult chimpanzees fed on 48 different plants and seven animal sources, most time on fruits and seeds, nuts, and leaves; and to a minor part on insects, plant pith and mammals. During the dry period chimpanzees increase feeding time on seeds and nuts, but reduce feeding on insects. Compared to males, females spent more time feeding on fruits, seeds, leaves, insects, and pith, but less on nuts, seeds and mammals.

“Understanding intraspecific feeding ecology and tooth wear patterns in chimpanzees is also a crucial first step for reconstructing the paleoecology of extinct hominins,” said Ellen Schulz-Kornas, who led the study at the former Max Planck Weizmann Center for Integrative Archaeology and Anthropology at the MPI-EVA in Leipzig. “When considering the findings of the present study it is conceivable that dust may have also triggered a decreased chewing efficiency, leading to dietary-physiological stress on the digestive system of fossil species,” Schulz-Kornas pointed out. “This may be especially important in seasonally fluctuating environments with an increased bias towards dry climate phases like for example in the South African early hominin record between 3.2 and 1.3 Million years ago,” concluded Schulz-Kornas.

Story Source:

Materials provided by Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology. Note: Content may be edited for style and length.

[ad_2]