[ad_1]

An elephant never forgets. This seems to be the case, at least, for elephants roaming about Namibia, looking for food, fresh water, and other resources.

The relationship between resource availability and wildlife movement patterns is essential to understanding species behavior and ecology. Landscapes can change from day-to-day and year-to-year, and many animals will move about according to resource availability. But do they remember past resource conditions? Just how important is memory and spatial cognition when seeking to understand wildlife movement?

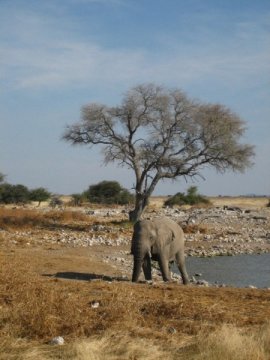

Researchers in Etosha National Park, Namibia, examined this question through an iconic mammal. “African elephants (Loxodonta africana) are ideal for this study — they have excellent cognitive abilities and long-term spatial memory,” lead author Miriam Tsalyuk of University of California Berkeley explained, “which helps them return to areas with better food and water. African savannas are unpredictable with a prolonged dry season, where knowledge of the long-term availability of resources is highly advantageous.” The study was published today in the Ecological Society of America’s journal Ecological Monographs.

Using GPS collars, the researchers tracked the movement of 15 elephant groups for periods ranging from 2 months up to a little over 4 and a half years. Key to this study, Tsalyuk emphasized, were satellite-based imagery and observations, which were used to create detailed data on vegetation types and biomass. Together with maps of surface water and human-made constructs, Tsalyuk and her colleagues then correlated these variables with the elephant movement data to look for patterns in behavior.

“Most ecological research to date examines how wildlife respond to the current environmental state,” she said. “However, animals use spatial and social memory to return to locations that have been beneficial in the past. Satellite imagery provides information about these past conditions and unravels the complexity of wildlife spatial use.”

Their analyses revealed that the elephants certainly seem to remember where to find the best food and reliable water. Long-term information (up to a decade) on forage conditions was a bigger factor in elephants’ decisions where to go than current conditions, particularly in the dry season.

“The results were very surprising indeed,” Tsalyuk said. “We thought that if we could capture the vegetation conditions as close as possible to the time the elephants passed there, we could better explain preference for a particular location. But we found the complete opposite — elephants have a stronger preference for locations where forage conditions have been better for many years, over the forage availability they see around them at the moment.”

The researchers were also surprised about the variability of the elephants’ preference for resources — different vegetation types and water sources — over time of day and over seasons.

Elephants’ strong inclination to be close to water is expected in the semiarid environment of Etosha. Preference for permanent water sources increases as rainfall declines. As the dry season progresses, elephants become increasingly dependent on artificial (human-made) water sources, such as bore holes.

Somewhat less expected was the elephants’ fondness to walk close to roads.

“Roads are often dangerous to wildlife,” Tsalyuk said. “However, this research was performed within Etosha National Park, where most of the roads are dirt roads with relatively little traffic.” Elephants highly preferred to travel along roads in the dry season, when road conditions are best and when the elephants need to move farther between water and vegetation resources. It seems they use roads as easy walking terrain to conserve energy.

It’s possible that they may also take advantage of browsable plants in roadside ditches, or could position themselves behind tourist vehicles as a potential shield from predators.

The elephants in Etosha prefer areas with higher grass biomass, but lower tree biomass. When food is abundant, the elephants feel more comfortable to explore the landscape for greener patches or higher quality forage. In the dry season, however, when food becomes scarcer and less nutritious the goal becomes reducing the risk of starvation, and the elephants restrict themselves to areas where forage productivity has been favorable for many years.

Elephants are important ecosystem engineers — they control habitat conditions or availability of resources to other organisms. For example, they enhance plant diversity by suppressing tree cover and promote seed dispersal and nutrient transport, while dense elephant populations may cause vegetation degradation and tree damage. Unfortunately for these integral animals, elephant populations throughout Africa are in steep decline in the last decade due to poaching and greater restriction of their range.

If we want to better understand the changes in elephant-savanna vegetation dynamics and to improve land management, it is crucial to account for the variation in the movement-related responses of elephants to changing resources.

[ad_2]