[ad_1]

A team of engineers and physicians in San Diego have developed a device that diffuses potent disinfectants for airborne delivery. Notably, the device works on a range of disinfectants that have never been atomized before, such as Triethylene glycol, or TEG.

In a study published in the August issue of Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology, the team used the device to atomize disinfectants onto environmental surfaces contaminated with bacteria and showed that it effectively eliminated 100 percent of bacteria that commonly cause hospital-acquired infections. In addition, atomized bleach solution, ethanol and TEG completely eliminated highly multi-drug resistant strains of bacteria including K. pneumoniae.

“Cleaning and disinfecting environmental surfaces in healthcare facilities is a critical infection prevention and control practice,” said Dr. Monika Kumaraswamy, a physician scientist at the University of California San Diego, hospital epidemiologist at the VA San Diego Healthcare System and corresponding author on the paper. “This device will make it much easier to keep hospital rooms clean.”

Researchers point out that one in 25 patients who checked into hospitals in 2011 (the last year for which data was available) had to prolong their stay because of healthcare-related infections developed within the hospital.

The technology has broader potential applications too. It could be used to deliver a whole new class of medicines to patients via inhalers.

“Our goal is to make injectable treatments inhalable,” said James Friend, a professor of mechanical engineering at the UC San Diego Jacobs School of Engineering and one of the paper’s authors.

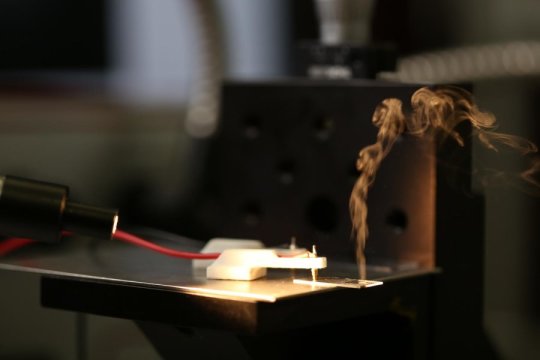

Researchers built the device using off-the-shelf smartphone components that produce acoustic waves. In phones, these parts are used mainly to filter wireless cellular signals and identify and filter voice and data information.

In this study, researchers used the smartphone components to generate sound waves at extremely high frequencies — ranging from 100 million to 10 billion hertz — in order to create fluid capillary waves, which in turn emit droplets and generate mist. This process is called atomization.

Currently, fluids can be atomized by mechanical means like in perfume and cologne sprayers, or by using ultrasound. But these methods either don’t work well with viscous fluids, require too much power, or break down some of the fluids’ active ingredients. They also require expensive equipment.

The technology used in this paper doesn’t have these drawbacks. That’s because the smart phone components use Lithium Niobate, or LN, a material that produces more energy efficient and more reliable ultrasonic vibrations. As a result, the device can atomize even the most viscous fluids into a fine mist that can drift in the air for more than an hour.

The device was built by Friend’s research group and tested in the laboratory of Dr. Victor Nizet at the UC San Diego School of Medicine, in experiments led by Kumaraswamy.

Although the device worked well on pneumonia-causing bacteria and on various multi-drug resistant strains of other pathogens, atomized TEG did not eliminate MRSA, much to the researchers’ surprise. “People told us TEG kills everything,” Friend said. “Well that’s just not true: in atomized droplet form, it was not all that effective at doing away with MRSA.”

Researchers are now working on building an updated prototype to use in a hospital setting, a process that they expect to take one or two years. The device also could be used in airports, airplanes and in public transportation during flu season, for example.

Story Source:

Materials provided by University of California – San Diego. Note: Content may be edited for style and length.

[ad_2]