[ad_1]

Researchers in Sweden using computed tomography (CT) have successfully imaged the soft tissue of an ancient Egyptian mummy’s hand down to a microscopic level, according to a study published in the journal Radiology.

Non-destructive imaging of human and animal mummies with X-rays and CT has been a boon to the fields of archaeology and paleopathology, or the study of ancient diseases. Imaging studies have contributed to a better knowledge of life and death in ancient times and have the potential to improve our understanding of modern diseases.

Both X-ray and conventional CT take advantage of the fact that materials absorb different amounts of X-rays. This phenomenon, known as absorption contrast, creates different degrees of contrast within an image.

“For studying bone and other hard, dense materials, absorption contrast works well, but for soft tissues the absorption contrast is too low to provide detailed information,” said Jenny Romell, M.Sc., from KTH Royal Institute of Technology/Albanova University Center in Stockholm, Sweden. “This is why we instead propose propagation-based phase-contrast imaging.”

Propagation-based imaging enhances the contrast of X-ray images by detecting both the absorption and phase shift that occurs as X-rays pass through a sample. The phase effect with X-rays is similar to how a ray of light changes direction as it passes through a lens. Capturing both absorption and phase shift provides higher contrast for soft tissues.

“There is a risk of missing traces of diseases only preserved within the soft tissue if only absorption-contrast imaging is used,” Romell said. “With phase-contrast imaging, however, the soft tissue structures can be imaged down to cellular resolution, which opens up the opportunity for detailed analysis of the soft tissues.”

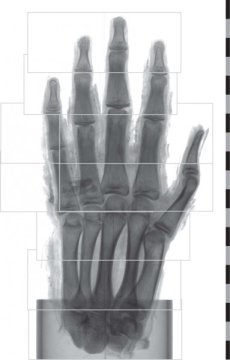

Romell and colleagues evaluated phase-contrast CT by imaging a mummified human right hand from ancient Egypt. The hand, today in the collection of the Museum of Mediterranean and Near Eastern Antiquities, was brought to Sweden at the end of the 19th century, along with other mummified body parts and a fragment of mummy cartonnage (papier-mâché case). The cartonnage belonged to an Egyptian man and has been dated to around 400 BCE (before common era). They scanned the entire hand and then performed a detailed scan of the tip of the middle finger.

The estimated resolution of the final images was between 6 to 9 micrometers, or slightly more than the width of a human red blood cell. Researchers were able to see the remains of adipose cells, blood vessels and nerves; they were even able to detect blood vessels in the nail bed and distinguish the different layers of the skin.

“With phase-contrast CT, ancient soft tissues can be imaged in a way that we have never seen before,” Romell said.

The findings point the way to a role for phase-contrast CT as an adjunct or alternative to invasive methods used in soft-tissue paleopathology that require extraction and chemical processing of the tissue. Due to their potentially destructive nature, these methods are undesirable or unacceptable for the analysis of many old and fragile specimens.

“Just as conventional CT has become a standard procedure in the investigation of mummies and other ancient remains, we see phase-contrast CT as a natural complement to the existing methods,” Romell said. “We hope that phase-contrast CT will find its way to the medical researchers and archaeologists who have long struggled to retrieve information from soft tissues, and that a widespread use of the phase-contrast method will lead to new discoveries in the field of paleopathology.”

Story Source:

Materials provided by Radiological Society of North America. Note: Content may be edited for style and length.

[ad_2]