[ad_1]

The amoeba Naegleria fowleri is commonly found in warm swimming pools, lakes and rivers. On rare occasions, the amoeba can infect a healthy person and cause severe primary amebic meningoencephalitis, a “brain-eating” disease that is almost always fatal. Other than trial-and-error with general antifungal medications, there are no treatments for the infection.

Researchers at Skaggs School of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences at University of California San Diego have now identified three new molecular drug targets in N. fowleri and a number of drugs that are able to inhibit the amoeba’s growth in a laboratory dish. Several of these drugs are already approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for other uses, such as antifungal agents, the breast cancer drug tamoxifen and antidepressant Prozac.

Their findings are published September 13 in PLoS Pathogens.

“Not many drugs can cross the blood-brain barrier,” said senior author Larissa Podust, PhD, associate professor at Skaggs School of Pharmacy. “Even if a drug can inhibit or kill the amoeba in a dish, it will not work in a host animal if it does not make it into the brain. That’s why we started with drugs known for their brain effects.” Podust led the study with co-first authors Anjan Debnath, PhD, assistant professor at Skaggs School of Pharmacy, and Wenxu Zhou, PhD, of Texas Tech University.

Podust and team began by investigating N. fowleri’s sterol biosynthesis pathway — a series of enzymes that build the amoeba’s outer membrane. They inhibited three of these enzymes to see how it would affect the organism’s viability. The researchers found that all three enzymes might make good drug targets. One of these, a sterol isomerase, is similar to a human receptor known to play a role in human neurological conditions, such as addiction, amnesia, pain and depression.

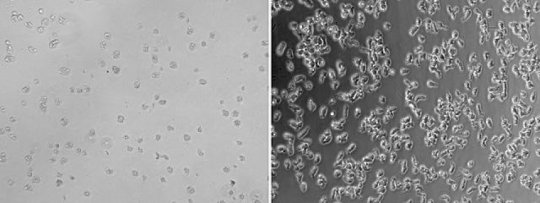

The researchers then tested a number of drugs already known to inhibit these enzymes for their ability to inhibit N. fowleri growth in the lab. All 13 of the new drugs they tested were more potent than miltefosine, an investigational drug currently recommended by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) for the treatment of primary amebic meningoencephalitis, in combination with other medications.

For example, while it takes 54.5 micromolar (?M) of miltefosine to arrest the growth of half the amoebae growing in a dish, it only took 5.8 ?M of tamoxifen and 31.8 ?M of Prozac. Tamoxifen and Prozac inhibit two different enzymes in N. fowleri’s sterol biosynthesis pathway. When the researchers combined a lower dose of tamoxifen with drugs that inhibit other enzymes in the sterol biosynthesis pathway, they were able to inhibit the growth of 95 percent of N. fowleri. In other words, combination treatment allowed them to inhibit more of the pathogen using lower drug concentrations.

“Drug repurposing is a relevant strategy for this infection because there is little economic incentive for the pharmaceutical industry to develop new drugs to treat these rare diseases,” Debnath said. “Already-approved drugs can also lessen the time and expense required to develop a drug from the laboratory to the clinic.”

According to the CDC, only four of 143 people known to be infected with N. fowleri in the U.S. from 1962 to 2017 have survived. However, the number of the university laboratories conducting research on N. fowleri is few, partly due to a liability for laboratory safety risks. The Center for Discovery and Innovation in Parasitic Diseases at Skaggs School of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences at UC San Diego is home to just one of six university-based laboratories worldwide conducting drug discovery research on live N. fowleri, and, based on current publications, the only university in the U.S. with a mouse model of the infection.

Story Source:

Materials provided by University of California – San Diego. Note: Content may be edited for style and length.

[ad_2]