[ad_1]

Columbia University biomedical researchers have captured close-up views of TRPV3, a skin-cell ion channel that plays important roles in sensing temperature, itch, and pain.

In humans, defects in the protein can lead to skin diseases such as atopic dermatitis (a type of eczema), vitiligo (uneven skin coloration), skin cancer, and rosacea.

All vertebrate DNA, including the woolly mammoth genome, contains the TRPV3 gene. Though the mammoths lived in extremely cold environments, they descended from elephants that lived in the tropics. Researchers think that changes in the TRPV3 genes of mammoths may have helped them withstand lower temperatures.

Alexander Sobolevsky’s lab at Columbia University Irving Medical Center used a powerful imaging technique called cryo-electron microscopy to take pictures of TRPV3 molecules. Initial 2D images were collected by freezing the molecules in an extremely thin, clear layer of ice and bombarding them with electrons. The researchers then used computational tools to convert the 2D images into detailed molecular 3D models.

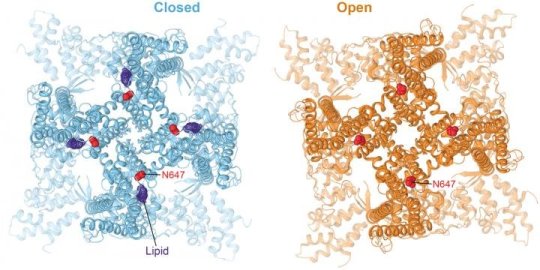

Image of human TRPV3 in the closed and open states viewed from outside the cell. Location of the region (N647) that is mutated in mammoths is highlighted. Images: Alexander Sobolevsky / CUIMC

This is the first time scientists have gotten a glimpse of TRPV3 in atomic detail. The researchers were able to get images of the protein in two states, revealing how the channel opens and closes to let ions flow into skin cells.

This exchange of ions prompts the body to react to sensations such as pain, itchiness, and changes in temperature. The group also discovered how a small molecule with anti-cancer properties called 2-APB interacts with and controls the function of this channel.

The structures in this study provide clues about how mutations in TRPV3 affect the channel’s ability to sense temperature and show that lipids — molecules that make up most of the cell membrane — contact the channel in several regions. Mammoth TRPV3 contains a mutation in one of these lipid-touching regions.

“Temperature affects the interaction of lipids and proteins,” Sobolevsky says. “A mutation in the woolly mammoth channel would most likely affect this interaction and could explain how these animals adapted to their cold environment.”

Researchers will use the structure to investigate how atomic changes to the protein cause it to malfunction in human diseases. “This study gives scientists a template they can use to design more effective drugs for treating these skin-related illnesses,” said Appu Singh, PhD, a postdoctoral fellow in the Sobolevsky lab and a first author of the paper.

Alexander Sobolevsky, PhD, is an associate professor of biochemistry and molecular biophysics at Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons.

Story Source:

Materials provided by Columbia University Irving Medical Center. Note: Content may be edited for style and length.

[ad_2]