Scientists from the University of Bonn: Even Tyrannosaurus rex could have suffered a slipped disc

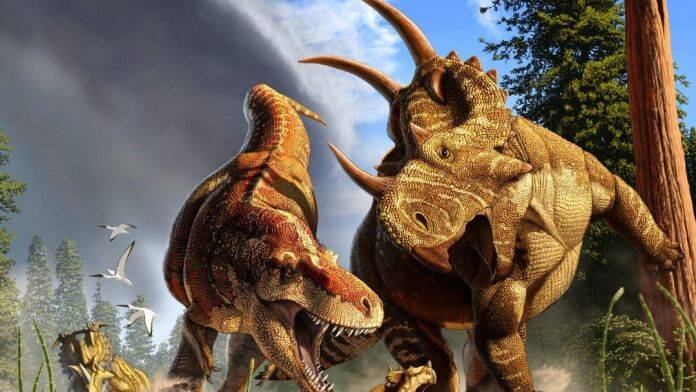

The intervertebral discs connect the vertebrae and give the spine its mobility. The disc consists of a cartilaginous fibrous ring and a gelatinous core as a buffer. It has always been assumed that only humans and other mammals have discs. A misconception, as a research team under the leadership of the University of Bonn has now discovered: Even Tyrannosaurus rex could have suffered a slipped disc. The results have now been published in the journal “Scientific Reports”.

Present-day snakes and other reptiles do not have intervertebral discs; instead, their vertebrae are connected with so-called ball-and-socket joints. Here, the ball-shaped end surface of a vertebra fits into a cup-shaped depression of the adjacent vertebra, similar to a human hip joint. In-between there is cartilage and synovial fluid to keep the joint mobile. This evolutionary construction is good for today’s reptiles, because it prevents the dreaded slipped disc, which is caused by parts of the disc slipping out into the spinal canal.

“I found it hard to believe that ancient reptiles did not have intervertebral discs,” says paleontologist Dr. Tanja Wintrich from the Section Paleontology in the Institute of Geosciences of the University of Bonn. She noticed that the vertebrae of most dinosaurs and ancient marine reptiles look very similar to those of humans – that is, they do not have ball-and-socket joints. She therefore wondered whether extinct reptiles had intervertebral discs, but had “replaced” these with ball-and-socket joints in the course of evolution.

Comparison of the vertebrae of dinosaurs with animals still alive today

To this end, the team of researchers led by Tanja Wintrich and with the participation of the University of Cologne and the TU Bergakademie Freiberg as well as researchers from Canada and Russia examined a total of 19 different dinosaurs, other extinct reptiles, and animals still alive today. The researchers concluded that intervertebral discs not only occur in mammals. For these investigations, vertebrae still in connection were analyzed using various methods.

Surprisingly, Dr. Wintrich has now also been able to demonstrate that remnants of cartilage and even other parts of the intervertebral disc are almost always preserved in such ancient specimens, including marine reptiles like ichthyosaurs and dinosaurs like Tyrannosaurus. She then traced the evolution of the soft tissues between the vertebrae along the family tree of land animals, which 310 million years ago split into the mammalian line and the dinosaur and bird line.

Intervertebral discs emerged several times during evolution

It was previously unknown that intervertebral discs are a very ancient feature. The findings also show that intervertebral discs evolved several times during evolution in different animals, and were probably replaced by ball-and-socket joints twice in reptiles. “The reason why the intervertebral disc was replaced might be that it is more susceptible to damage than a ball-and-socket joint,” says Dr. Wintrich. Nonetheless, mammals have always retained intervertebral discs, repeating the familiar pattern that they are rather limited in their evolutionary flexibility. “This insight is also central to the medical understanding of humans. The human body is not perfect, and its diseases reflect our long evolutionary history,” adds paleontologist Prof. Dr. Martin Sander from the University of Bonn.

In terms of research methods, the team drew not only on paleontology, but also on medical anatomy, developmental biology and zoology. Under the microscope, dinosaur bones cut with a rock saw and then ground very thinly provide information comparable to histological sections of fixed and embedded tissue of extant animals. This makes it possible to bridge the long periods of evolution and identify developmental processes. Prof. Sander remarks: “It’s truly amazing that the cartilage of the joint and apparently even the disc itself can survive for hundreds of millions of years.”

Dr. Wintrich, who now works at the Institute of Anatomy of the University of Bonn, is pleased about the cooperation between the fields that has made this interdisciplinary understanding possible in the first place: “We found that even Tyrannosaurus rex was not protected against slipped discs.” Only bird-like predatory dinosaurs then evolved ball-and-socket joints as well and saddle joints, still seen in today’s birds. Likewise, such ball-and-socket joints were a decisive advantage for the stability of the spine of the largest dinosaurs, the long-necked dinosaurs.

This bridge between paleontology and medicine is seminal in Germany. The anatomist Prof. Dr. Karl Schilling from the University of Bonn, who was not involved in the new study, reports: “In the USA, in contrast, dinosaur researchers and evolutionary biologists are often closely involved in medical training, especially in anatomy and embryology. This gives young doctors a perspective that is becoming increasingly important in a rapidly changing environment.”