The construction of an optical atomic clock has been completed at the National Laboratory of Atomic, Molecular and Optical Physics. The clock is a joint effort of scientists from three Polish higher education institutions: University of Warsaw, Jagiellonian University, and Nicolaus Copernicus University. The new clock, which is the first one in Poland and one of several in the world, will help to precisely measure time.

The device occupies four rooms at the National Laboratory of Atomic, Molecular and Optical Physics in Toruń. It was designed and built by a team of scientists from three Polish higher education institutions: University of Warsaw (the project’s coordinator), Jagiellonian University, and Nicolaus Copernicus University.

The clock’s theoretical stability stems from the fact that the physical processes and mechanisms used in its design only allow it to skip a second once every several billion years, which is a significantly longer period than the one which started with the Big Bang.

“Such stability is, for now, beyond our reach, as it requires years of careful calibration and improvement, like any other high precision measurement device. However, even now, at the very beginning of our work, we have achieved higher stability than it is required by the International Bureau of Weights and Measures in Paris,” said Dr hab. Roman Ciuryło, head of the Toruń laboratory.

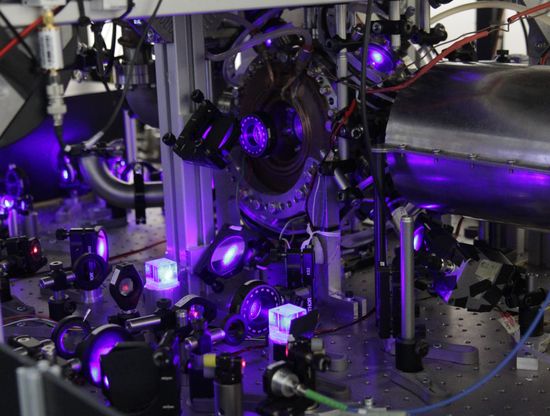

Optical atomic clocks are composed of an atomic frequency standard, a frequency comb, and high precision laser. The light frequency of the laser is carefully adjusted to the energy difference between precisely determined points in the frequency standard. Time is measured by observing the oscillations of electromagnetic field in calibrated and stabilized laser. The laser’s frequency, however, is so high that counting every oscillation is impossible for today’s electronic devices. The gears in traditional clock are replaced by a frequency comb, which generates a series of short, rapid impulses. They serve as a kind of “ruler,” which can be synchronized with the frequency of light adjusted to the frequency standard.

“The most precise measurement require constant comparisons with other clocks, so we built two independent clocks. This way we can better correct the clock’s measurements,” said. Dr hab. Michał Zawada.

Both frequency standards can operate using the atoms of Strontium 88, but one of them may be operated using Strontium 87 to avoid miscalculations. In each standard, strontium atoms are isolated and cooled to the temperature of 10 micro-Kelvins in a ultra-high vacuum chamber, trapped in specially designed optical tweezers.

Because the clock has been developed relatively recently, the scientists have not yet been able to fully measure and describe all its properties. However, the data collected so far suggests that it is the most stable and precise clock in Poland.

“We succeeded because of fantastic management and cooperation between all three universities. It was a logistic challenge, since one of the standards was constructed in Kraków and had to be transported to Toruń, but it turned out fine in the end. Thanks to our cooperation, we have a unique device which apart from measurements may be used in sophisticated experiments in the fields of nuclear physics, molecular physics, and quantum optics,” said Prof. Wojciech Gawlik from the JU Institute of Physics.

Precise measurements are crucial in many areas of science and technology. The most complex clocks help physicists to test such fundamental properties of the world as the change of properties of physical bodies over time, relativity theory, and the search for dark matter. in space. Atomic clocks from the previous generation are much less precise and are currently used in satellite navigation, high-capacity wireless networks, bank transfers and Earth gravity field measurements.