To explore the outer regions of the Solar System, space probes such as Voyager 1 and 2, Cassini-Huygens and New Horizons were sent on long expeditions. Now a German-Hungarian research group, led by Örs H. Detre of the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy (MPIA) in Heidelberg, shows that with the appropriate technology and ingenuity, interesting results can also be achieved with observations from far away.

The scientists used data from the Herschel Space Observatory, which was deployed between 2009 and 2013 and in whose development and operation MPIA was also significantly involved. Compared to its predecessors that covered a similar spectral range, the observations of this telescope were significantly sharper. It was named after the astronomer William Herschel, who found infrared radiation in 1800. A few years earlier, he also discovered the planet Uranus and two of its moons (Titania and Oberon), which now have been explored in greater detail along with three other moons (Miranda, Ariel and Umbriel).

The discovery of the moons in the Herschel data was a coincidence

“Actually, we carried out the observations to measure the influence of very bright infrared sources such as Uranus on the camera detector,” explains co-author Ulrich Klaas, who headed the working group of the PACS camera of the Herschel Space Observatory at MPIA with which the images were taken. “We discovered the moons only by chance as additional nodes in the planet’s extremely bright signal.” The PACS camera, which was developed under the leadership of the Max Planck Institute for Extraterrestrial Physics (MPE) in Garching, was sensitive to wavelengths between 70 and 160 µm. This is more than a hundred times greater than the wavelength of visible light. As a result, the images from the similarly sized Hubble Space Telescope are about a hundred times sharper.

Cold objects radiate very brightly in this spectral range, such as Uranus and its five main moons, which – warmed by the Sun – reach temperatures between about 60 and 80 K (–213 to –193 °C).

“The timing of the observation was also a stroke of luck,” explains Thomas Müller from MPE. The rotational axis of Uranus, and thus also the orbital plane of the moons, is unusually inclined towards their orbit around the Sun. While Uranus orbits the Sun for several decades, it is mainly either the northern or the southern hemisphere that is illuminated by the Sun. “During the observations, however, the position was so favourable that the equatorial regions benefited from the solar irradiation. This enabled us to measure how well the heat is retained in a surface as it moves to the night side due to the rotation of the moon. This taught us a lot about the nature of the material,” explains Müller, who calculated the models for this study. From this he derived thermal and physical properties of the moons.

When the space probe Voyager 2 passed Uranus in 1986, the constellation was much less favourable. The scientific instruments could only capture the south pole regions of Uranus and the moons.

The moons resemble the dwarf planets at the edge of the Solar System

Müller found that these surfaces store heat unexpectedly well and cool down comparatively slowly. Astronomers know this behaviour from compact objects with a rough, icy surface. That is why the scientists assume that these moons are celestial bodies similar to the dwarf planets at the edge of the Solar System, such as Pluto or Haumea. Independent studies of some of the outer, irregular Uranian moons, which are also based on observations with PACS/Herschel, indicate that they have different thermal properties. These moons show characteristics of the smaller and loosely bound Transneptunian Objects, which are located in a zone beyond the planet Neptune. “This would also fit with the speculations about the origin of the irregular moons,” adds Müller. “Because of their chaotic orbits, it is assumed that they were captured by the Uranian system only at a later date.”

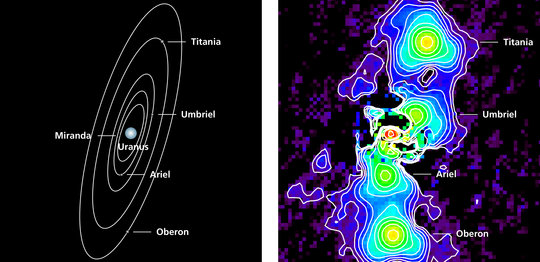

However, the five main moons were almost overlooked. In particular, very bright objects such as Uranus generate strong artifacts in the PACS/Herschel data, which cause some of the infrared light in the images to be distributed over large areas. This is hardly noticeable when observing faint celestial objects. With Uranus, however, it is even more pronounced. “The moons, which are between 500 and 7400 times fainter, are at such a small distance from Uranus that they merge with the similarly bright artifacts. Only the brightest moons, Titania and Oberon, stand out a little from the surrounding glare,” co-author Gábor Marton from Konkoly Observatory in Budapest describes the challenge.

This accidental discovery spurred Örs H. Detre to make the moons more visible so that their brightness could be reliably measured. “In similar cases, such as the search for exoplanets, we use coronagraphs to mask their bright central star,” Detre explains. “Herschel did not have such a device. Instead, we took advantage of the outstanding photometric stability of the PACS instrument.” Based on this stability and after calculating the exact positions of the moons at the time of the observations, he developed a method that allowed him to remove Uranus from the data. “We were all surprised when four moons clearly appeared on the images, and we could even detect Miranda, the smallest and innermost of the five largest Uranian moons,” Detre concludes.

“The result demonstrates that we don’t always need elaborate planetary space missions to gain new insights into the Solar System,“ co-author Hendrik Linz from MPIA points out. “In addition, the new algorithm could be applied to further observations which have been collected in large numbers in the electronic data archive of the European Space Agency ESA. Who knows what surprise is still waiting for us there?”