A groundbreaking study published today in the Journal of Human Evolution sheds new light on the lives of Ice Age adolescents, revealing that their experiences of puberty were strikingly similar to those of modern teens. This research, which delves into the timing and progression of puberty among Pleistocene teenagers, addresses a significant knowledge gap in our understanding of early human development.

Ancient Bones Illuminate Adolescent Development

The study, led by paleoanthropologist April Nowell from the University of Victoria (UVic), analyzed the bones of 13 ancient individuals aged between 10 and 20 years. Researchers used specific markers in these bones to assess the stages of adolescence. The study’s lead author, Mary Lewis from the University of Reading, employed a novel technique to evaluate mineralization in canines and maturation in bones of the hand, elbow, wrist, neck, and pelvis. This method allowed the researchers to estimate the progression of puberty at the time of death.

“This is the first application of my puberty stage estimation method to Paleolithic fossils and the oldest use of peptide analysis for biological sex estimation,” Lewis remarked. Her technique provides insights into physiological changes such as menstruation and voice deepening, linking ancient adolescents’ developmental stages to their modern counterparts.

Revising Views on Ice Age Health and Development

Contrary to the harsh view of prehistory as “nasty, brutish, and short,” this study reveals that Ice Age adolescents were relatively healthy. The findings suggest that most individuals entered puberty around 13.5 years old and reached full adulthood between 17 and 22 years, indicating a comparable onset of puberty to that of modern teens in affluent societies.

“It can be challenging to connect with the distant past, but our shared experience of puberty creates a bridge,” Nowell noted. “This research humanizes these ancient individuals in a way that studying artifacts alone cannot.”

Insight into Individual Lives

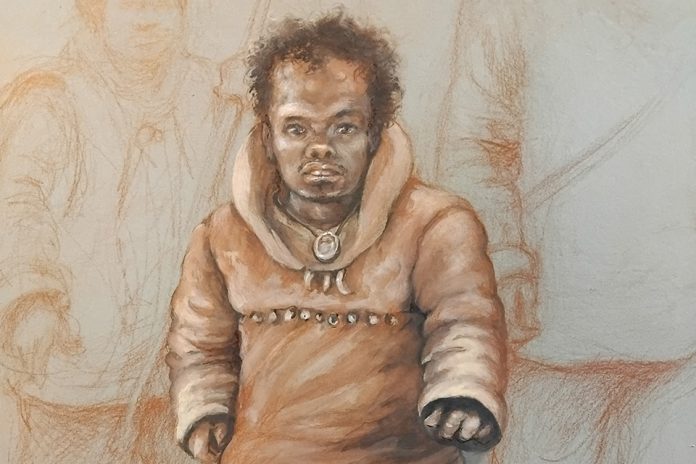

One of the notable subjects of the study was “Romito 2,” an adolescent with a form of dwarfism. The study offers new information about Romito 2’s physical appearance and social role. Despite being in the midst of puberty, his voice would have been deeper, and he would have had the ability to father children. However, his short stature might have led to a youthful appearance, influencing how he was perceived by his community.

“The detailed insights into the physical appearance and developmental stages of these Ice Age adolescents offer a fresh perspective on their burials and social roles,” said Jennifer French, an archaeologist at the University of Liverpool and co-author of the study.

International Collaboration and Future Research

This study was a collaborative effort involving researchers from UVic (Canada), the University of Reading and University of Liverpool (UK), the Museum of Prehistoric Anthropology of Monaco (Monaco), and the universities of Cagliari and Siena (Italy). The research was supported by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council, alongside Nowell’s Lansdowne Fellowship Award.

The collaborative team continues to explore the lives and social roles of Ice Age teenagers, promising further revelations about our ancient ancestors.

This new research not only provides valuable information about early human puberty but also helps us understand the developmental experiences shared across millennia.