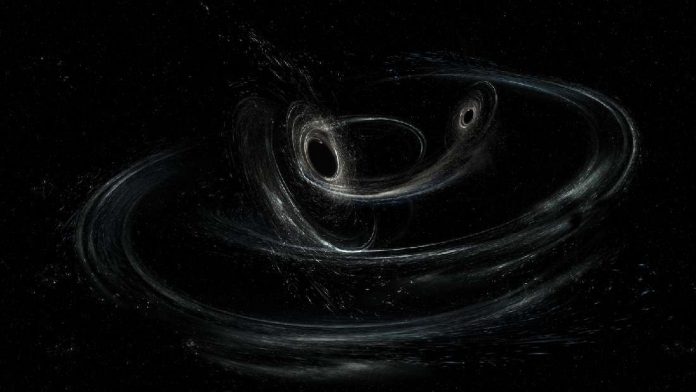

Gravitational waves have so far been detected from merging black holes and merging neutron stars, but some researchers have their eyes on a much bigger target: supermassive black holes. There’s one big problem standing in their way, however. Supermassive black holes produce waves with a frequency in the order of nanohertz, way below what we can currently measure with the observatories we have.

To overcome this obstacle, a group of researchers has suggested using other astronomical objects: pulsars. A pulsar is a specific type of neutron star that has a strong magnetic field, spins very fast around its axis, and emits extremely regular pulsations. A gravitational wave passing between us and the pulsar would affect the signal, which means it could be seen in that way.

By observing many of these pulsars at the same time, the team considers it likely that we will observe the gravitational waves from supermassive black holes binaries within the next 10 years. According to the study, published in Nature Astronomy, there should be about 100 sources within a detectable distance.

“The strongest gravitational wave sources in the universe are supermassive black holes in binary systems,” lead author Dr Chiara Mingarelli told IFLScience. “Unlike the stellar-mass black holes LIGO is sensitive to, we know exactly where supermassive black holes live – in the hearts of massive galaxies. So, why not use this information to make predictions about specific sources?”

The international team of researchers used the 2 Micron All-Sky Survey to look at the potential sources of these nanohertz gravitational waves. They estimate that within a 730-million-light-year radius, around 91 sources should be constantly emitting gravitational waves and another seven are binaries that won’t ever collide with each other.

“My work is based on real galaxies, instead of simulated populations, and in this new work, my colleagues and I rank local galaxies in terms of the likeliest to host supermassive black hole binaries in the pulsar timing array (PTA) band,” Dr Mingarelli added. “We find that with International PTA efforts, nanohertz GWs from at least one nearby supermassive black hole binary should be detected.”

Gravitational waves distort space-time by compressing it in one direction while stretching it in another. This creates a small but measurable change to the light they encounter. Although this effect is tiny on the pulsar timing, researchers are confident that by combining the data from many pulsars, they can detect and reconstruct the gravitational wave.

The pulsars considered in the study are thousands of light-years away, which Dr Mingarelli said in a statement acts like a galactic-scale gravitational-wave detector. An observation of gravitational waves from a supermassive black hole would give us incredible insight into these objects.