Scientists have completed the first chromosomal-level genome sequence for a freshwater sponge. The research provides invaluable insight into the evolution of the 600 to 800 million year-old lineage, and could provide genetic tools to tackle challenges in maintaining clean freshwater and human health.

“This research provides an amazing window into the genetic features of early animals—and helps us understand how they lived, and became so successful,” said Sally Leys, professor in the Department of Biological Sciences and senior author.

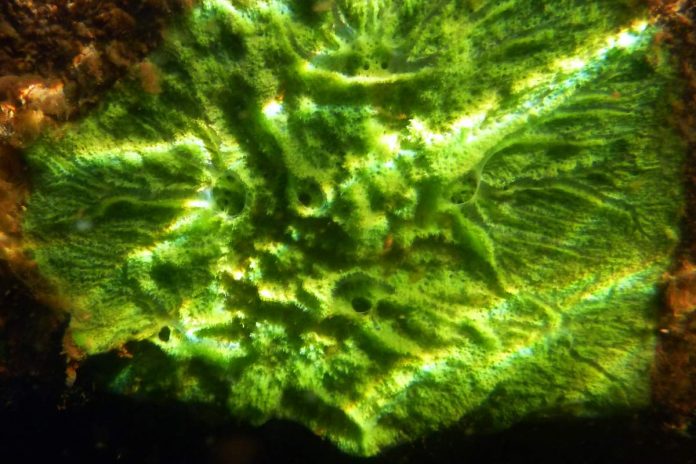

The sponge, called Ephydatia muelleri, can be found in freshwater across the northern hemisphere in almost any lake, river, pond, or canal. As filter feeders, freshwater sponges are integral for cleaning our waterways, and have evolved to live in extreme conditions over the last 30 million years.

“Sponges have almost twice as many genes as humans, and we only know what a fraction of these might do,” said Nathan Kenny, postdoctoral fellow at Oxford Brookes University in the United Kingdom, and first author on the paper.

“We don’t have to go to space to find things that are alien to us—we can look at what the novel genes in sponges are doing. And because sponges are related to us, though very distantly, we might discover tricks sponges use to deal with problems such as controlling cell growth or to protect themselves from harmful bacteria, which then could be used to treat human diseases.”

Currently, scientists have few tools to help assess what Earth’s earliest animals were like, or how some animals adjusted to live in freshwater after originating in the oceans. This research provides the foundational data that is critical for examining these problems in depth, including the near complete sequencing of the 23 individual chromosomes, as well as the identification of mechanisms that turn genes on or off and the method by which this sponge was able to transition to freshwater environments. The research also identifies tiny microorganisms that live inside the sponges, helping them survive in freshwater.

Funding for this research was provided by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) and a Horizon 2020 Marie Skłodowska-Curie Fellowship (MSCF)