Though mighty, the Milky Way and galaxies of similar mass are not without scars chronicling turbulent histories. University of California, Irvine astronomers and others have shown that clusters of supernovas can cause the birth of scattered, eccentrically orbiting suns in outer stellar halos, upending commonly held notions of how star systems have formed and evolved over billions of years.

Hyper-realistic, cosmologically self-consistent computer simulations from the Feedback in Realistic Environments 2 project enabled the scientists to model the disruptions in otherwise orderly galactic rotations. The team’s work is the subject of a study published today in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

“These highly accurate numerical simulations have shown us that it’s likely the Milky Way has been launching stars in circumgalactic space in outflows triggered by supernova explosions,” said senior author James Bullock, dean of UCI’s School of Physical Sciences and a professor of physics & astronomy. “It’s fascinating, because when multiple big stars die, the resulting energy can expel gas from the galaxy, which in turn cools, causing new stars to be born.”

Bullock said the diffuse distribution of stars in the stellar halo that extends far outside the classical disk of a galaxy is where the “archeological record” of the system exists. Astronomers have long assumed that galaxies are assembled over lengthy periods of time as smaller star groupings come in and are dismembered by the larger body, a process that ejects some stars into distant orbits. But the UCI team is proposing “supernova feedback” as a different source for as many as 40 percent of these outer-halo stars.

Lead author Sijie Yu, a UCI Ph.D. candidate in physics, said the findings were made possible partly by the availability of a powerful new set of tools.

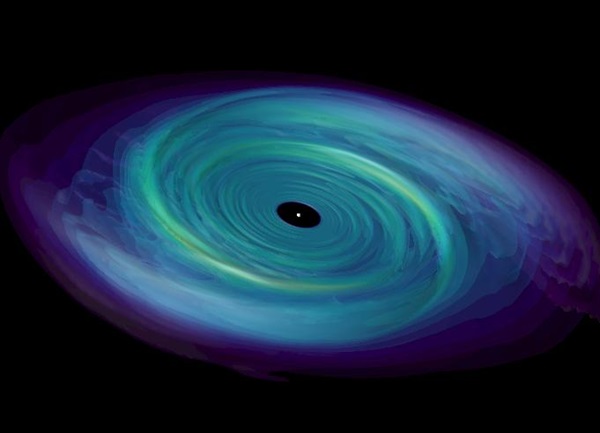

“The FIRE-2 simulations allow us to generate movies that make it seem as though you’re observing a real galaxy,” she noted. “They show us that as the galaxy center is rotating, a bubble driven by supernova feedback is developing with stars forming at its edge. It looks as though the stars are being kicked out from the center.”

Bullock said he did not expect to see such an arrangement because stars are such tight, incredibly dense balls that are generally not subject to being moved relative to the background of space. “Instead, what we’re witnessing is gas being pushed around,” he said, “and that gas subsequently cools and makes stars on its way out.”

The researchers said that while their conclusions have been drawn from simulations of galaxies forming, growing and evolving to the present day, there is actually a fair amount of observational evidence that stars are forming in outflows from galactic centers to their halos.

“In plots that compare data from the European Space Agency’s Gaia mission — which provides a 3D velocity chart of stars in the Milky Way — with other maps that show stellar density and metallicity, we can see structures similar to those produced by outflow stars in our simulations,” Yu said.

Bullock added that mature, heavier, metal-rich stars like our sun rotate around the center of the galaxy at a predictable speed and trajectory. But the low-metallicity stars, which have been subjected to fewer generations of fusion than our sun, can be seen rotating in the opposite direction.

He said that over the lifespan of a galaxy, the number of stars produced in supernova bubble outflows is small, around 2 percent. But during the parts of galaxies’ histories when starburst events are booming, as many as 20 percent of stars are being formed this way.

“There are some current projects looking at galaxies that are considered to be very ‘starbursting’ right now,” Yu said. “Some of the stars in these observations also look suspiciously like they’re getting ejected from the center.”

This project — which involved astronomers from UC Davis, UC San Diego, the University of Pennsylvania, the Flatiron Institute, The University of Texas at Austin, NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, the California Institute of Technology and Northwestern University — was supported by the National Science Foundation and the Heising-Simons Foundation.