Researchers from the University of Rochester in the US have resorted to quite an unusual source of information to estimate fluctuations of magnetic field of the Earth.

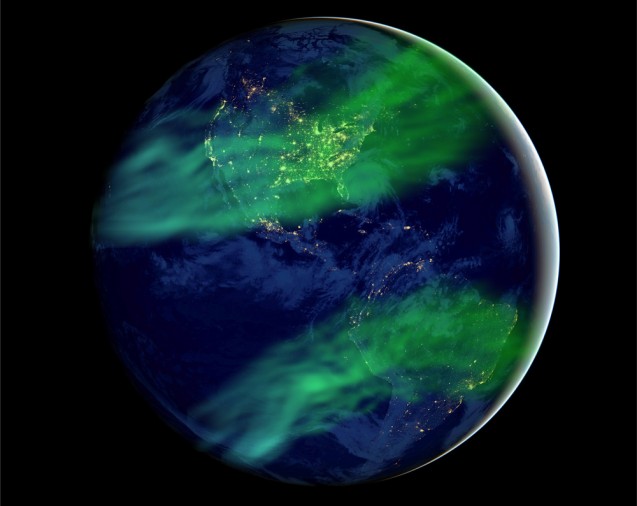

The South Atlantic Anomaly is a geomagnetic anomaly that stretches from South America to southern parts of Africa. This is where Earth’s magnetic field is the weakest, and, at sea level, equals 1,000 km above sea level in other parts of the world. If one puts a compass deep beneath South Africa, they will find that down there, despite being located in Southern Hemisphere, the compass will actually point north.

For the last 160 years, the strength of Earth’s magnetic field has been decreasing at what the scientists call an “alarming rate,” making scientists talk of an impending magnetic pole switch that could happen, but nobody actually knows when. However, such an occurrence would definitely lead to massive electric system disruptions, so it’s better to be prepared.

At present, it is impossible to jump to any conclusion or prediction without knowing the bigger picture: the last time the poles switched, the scientists say was 800,000 years ago. In other words, 160 years is just too small a time span to tell anything.

“We’ve known for quite some time that the magnetic field has been changing, but we didn’t really know if this was unusual for this region on a longer timescale, or whether it was normal,” says Vincent Hare, from the University of Rochester, the lead author of a paper published in Geophysical Research Letters.

In order to take a deeper look, the team of Rochester scientists, led by John Tarduno, a professor and chair of the Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences, turned towards an unusual source of information they found in South Africa.

It turns out, that during the Iron Age, Bantu-speaking tribes expanded in South Africa, and those tribes had an interesting custom: during the arid years, they burned some of their houses as a sacrifice, and those houses were made of clay. The clay includes magnetic particles, which change their positioning according to the Earth’s magnetic field. And when the house burns, the high temperature effectively cements those magnetic minerals in one position, EurekAlert reports.

By excavating clay samples and orienting them in the field, the researchers were able to measure the strength of magnetic field in South Africa. The research showed that the magnetic field fluctuated repeatedly in this region: the magnetic field has weakened in periods of 400-450 AD, 700-750 AD, and again 1225-1550 AD.

“We now know this unusual behavior has occurred at least a couple of times before the past 160 years, and is part of a bigger long-term pattern,” Hare says.

Despite significantly expanded historical retrospective, however, the scientists insist that current magnetic field weakening does not necessarily herald the much-dreaded magnetic pole switch.

“However, it’s simply too early to say for certain whether this behavior will lead to a full pole reversal.”

“We do not yet know if the current field is going to reverse in the next few thousand years, or simply continue to weaken over the next couple of centuries,” the Daily Mail writes on the issue.

Even if a complete pole reversal is not in the near future, however, the weakening of the magnetic field strength is intriguing to scientists, Tarduno says.

“The possibility of a continued decay in the strength of the magnetic field is a societal concern that merits continued study and monitoring.”