Most dinosaurs buried their eggs and hoped for the best, but some species—including a few hefty ones—built nests and pampered unhatched offspring much as birds do today, a new study reveals.

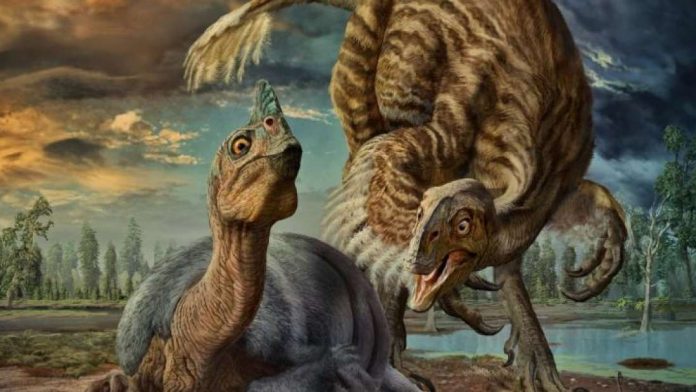

Once upon a time some 100 to 70 million years ago, two-legged bird-like dinosaurs weighing almost as much as the average car roamed North America alongside Tyrannosaurus rex. Nicknamed the “chicken from hell,” these enormous oviraptorosaurs brooded their eggs like their modern descendants today do, but with a “unique adaption” to keep from crushing them.

Dinosaurs in the group known as oviraptorosaurs differed hugely in size. Some weighed as little as 941 kilograms (90 pounds) to nearly 1,563 kilograms (3,500 pounds). Scientists examined 40 fossilized nests – technically called “clutches” because nests don’t fossilize – in diameters ranging from 40 centimeters (16 inches) to nearly 3.3 meters (11 feet) to reveal how these different body sizes might affect their nesting approaches.

In all cases, the eggs in a clutch were exposed in a way similar to brooding birds, but oviraptorosaurs eggs were arranged in a ring configuration. The clutch morphology varies; in smaller species, the center space is much smaller or not empty at all, but as the egg gets bigger so does the center space with the biggest species occupying most of the nest.

It’s in that empty space that scientists now believe the dino-mums would sit in order to avoid crushing the eggs while still maintaining some contact.

“Oviraptorosaurs appear to have adapted to sitting on their nests by somewhat modifying the clutch configuration as species increased in body size, probably because egg mass becomes relatively smaller and eggshell thickness (relative to egg mass) becomes relatively thinner, resulting in a structurally weaker egg,” the authors write in the study published in Biology Letters.

Modern birds are descended from a large group of carnivorous dinosaurs called theropods, which includes T. rex, that are thought to have laid eggs. But there is little evidence that therapods built nests, so studying oviraptorosaurs’ brooding habits is important. The ring configuration suggests the dinos were accounting for weight, and that the brooding may not have kept the eggs warm, but been a way of protecting them.

“This adaptation, not seen in birds, appears to remove the body size constraints of incubation behavior in giant oviraptorosaurs,” according to the study. “As in brooding birds, this behavior may have been related to protection, shelter or thermoregulation of the eggs in oviraptorosaurs.”

In recent years, researchers have found preserved eggs, skeletons, and even the fossilized remains of parents sitting on their nests.